Exhibition

Beyond the Margins

28 March to 17 June 2023

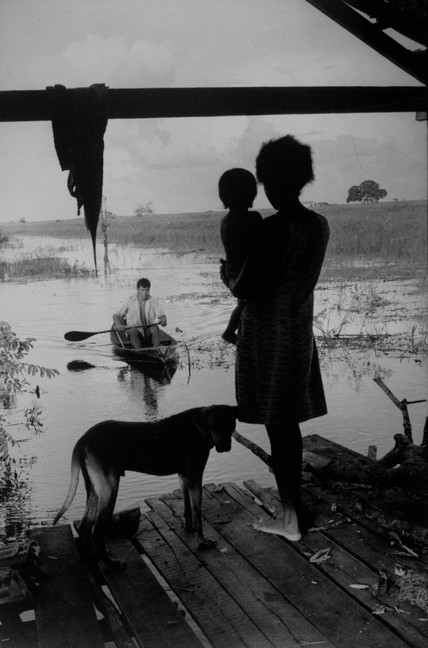

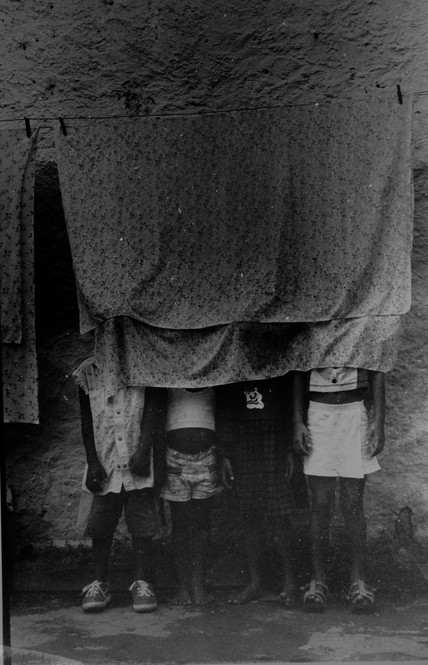

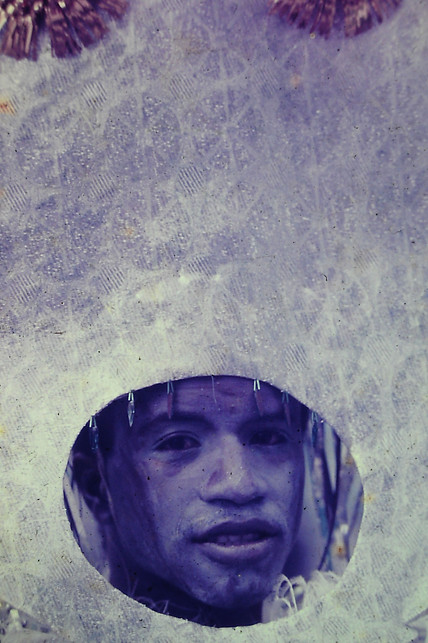

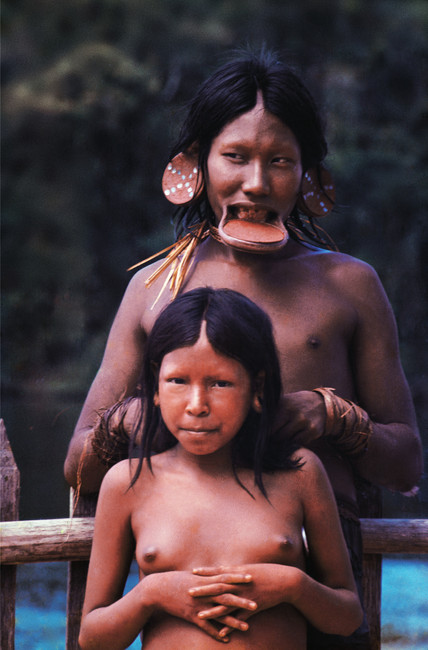

The preservation of the environment, for life on Earth, is among the greatest concerns and urgencies in the world today. Historically, the relationship between humanity and nature took several paths. Some of them allow us to renew our eyes and find other perspectives. This is the invitation that Vale and the Vale Cultural Institute made to visitors to the Brazilian Pavilion at ExpoDubai 2020: relive the paths taken by various Brazilian communities, registered by great names in photography. In the images captured, water shapes the landscape, shapes everyday life and leads the path of creation and resistance through the perpetuation of local and collective knowledge and identities.

Water is a constitutive part of the formation of individuals, and as a consequence of their education and culture. Water shapes the modes of existence – work, living, eating, moving, resting, partying, living and dying. Water gushes in the sea, in the river, in the travelers’ saddlebags, in the cookers’ pots, in the tears of children and old people. The images presented constitute the documentary panorama of those who inhabit the banks, and in addition to them, they thicken the basis of what we define as a nation. They are portraits of the human in the world, the protagonist in his struggle for everyday life.

Have a nice visit!

Beyond the Margins - Exhibition set up at ExpoDubai2020

Tour Virtual

From the liquidity of the thought and experience of the popular subject

Gabriel Gutierrez

(…)

Like everything real is thick.

That river is thick and real.

How thick an apple is.

Like a dog

is thicker than an apple.

How is it thicker

The dog’s blood

than the dog itself.

How is it thicker

A man

than the blood of a dog.

Since it is much thicker

The blood of a man

than a man’s dream.

(…)

João Cabral de Melo Neto, The Dog Without Feathers

The thinking of the popular man in the world flows like the course of a river. The reliefs and the route are necessary. Falls, barriers, and breaches delimit the field of reflection and practice that together advance through the crystallized bed of absences. When it appears calm, behind a meander, or impetuous, gushing from the top of a ravine, the river always emerges because it does not know its destination and recognizes the risks in its passage. Liquid, it fills the spaces surrounding the banks and establishes the limits of the dry world. Liquid, popular thought, brings together and absorbs what comes its way. It eats away at the banks, even if made up of them, altering the world around it.

Just as water finds its way through the experience of walking, the popular man draws life from the bifurcation between presence and experience, and his thinking presents itself as a lack of knowledge that allows him to encounter the origin of things. This non-continuous desire suspends historicist time, because each moment is the appropriate moment to originate. With this certainty, João Cabral de Melo Neto ends his poem The Dog Without Feathers, expressing the tipping point between life and human creation:

Thick,

Because it’s thicker

A Vida Que Se Fought

Every day

(like a bird

What goes on every second

conquering your flight)

Not everything is given, and the hidden part of existence is linked to the sphere of the impersonal, of which does not belong to them, but on the other hand belongs to a whole. For this reason, the popular man is not enough himself, and his work takes on dimensions of the collective scale and of the landscape, in their right measure.

The river feeds the land. It is where branches and roots hang, where herds and caravans head. Popular thought, because it presents itself as the proper structure of thought, nourishes all great achievements, great embroideries, heroic paintings, lavish kitchens served in fine porcelain. Everything originates from the popular, because those who work are the popular. I work as an ideal and practical thought. Thus, culture originates in the exercise of disruptive, incontinent, and irrepressible thought, as well as the human dimension of life.

Finally, popular thought is tragic because it knows about death. The relationship between the popular man and the world defines him as a tragic subject because he is ambivalently aware of his responsibility over the world, and his unavoidable condition of being finite. To know death is to know the landscape, the other and the present self. Just like the tightrope walker, it engenders its existence on the rope: everything below it is a precipice, and the balance to reach the other side lies in the every turn of the unicycle wheel and in the counterbalance of the umbrella that would never stop the possible fall, because those who are on the tightrope of thought know that the only real thing is the fall, foreshadowed by the very weight of those who, through the trick, deceive them.

Beyond the banks

The images that open at this moment to the visitor reflect, from the moment captured, the experience of the popular man in his existential epic. Intentionally, the images portray the individuals that inhabit Brazil. In their daily lives, they prepare food, bathe, celebrate the most diverse symbols and senses, and commune. Above all, they establish an original way of life with the landscape. Through abundance or scarcity, they express in gestures, objects, paths and encounters the impermanence of their thinking and physique, that is, the suspension of experience that directs all of the following, as in a prayer, which is always unique in the mouth of those who proclaim it. They are not images of facts, but accounts of a long thread that is woven and unwoven, signifying and uniting times and spaces.

The perpetual movement, recorded through the eyes of the various photographers gathered here, Brazilians from various backgrounds, pleasures us in a sensitive way, allowing us to find ourselves reflected in some corner of the wild, in body painting, wearing similar clothing, or refreshing us with water that, although never the same, satisfies us.

[1] CHAUI, Marilena. SaberXPower: In Search of the Space of Reflection, In: Conformism and Resistance. São Paulo: Perseus Abramo, 2018.

Possible articulations between experience, transcendence, and poetics

Ubiratã Trindade

The human condition is revealed by the awareness that, at all times, we are touched by the world. This condition produces, organizes, and confers authenticity to our subjectivity. The way we relate to others – everyone else – is a product of that experience. The place where we live, the landscape that surrounds us give us encouragement and, above all, present themselves as a mother cell. Sensitive experience precedes all elaborate knowledge. This is the result of the direct relationship between our senses and the environment.

The deep relationship with what surrounds us is what also gives materiality to the idea of genesis. We cannot stop ourselves from making sense, from creating. Everything is waiting for the triumph of saying something. From the symbiotic relationship with the world, we were born. Things shape us, organize our gestures and desires, our way of feeling and responding to different stimuli. It all depends on where we are, where we step on. And because of the density of the materials that our hands reach.

In our experience with the world, with the original materials, we understood the place of divinity from an early age. It is always in a violent awakening that these greatness overwhelm us with the perception of their insubordination. Even small, the desire to know and control them drives and conditions our existence. Full of senses, we set out towards what touches us, in an eternal circle, as befits a giving existence.

From the temperament of the waters, we commit to decipher their mysteries. And moved, in a state of childhood, we plunged into the experience, unaware and open to new possibilities of feeling and giving back. We classify their qualities and heights to give names to Encantados and Santos and divide powers between them into well-kept pieces, in order not to displease anyone and to be able to count on each one as necessary.

Devotion is creative sacrifice, the creation of worlds. It means putting a flag, feather, glass in a place where life is lacking, it is a sowing of meaning. Art of filling the hole. We set out to meet the joyful waters to put an end to our sorrows. We set out to meet the gods who drown and are reborn; who incarnate as animals; those born from the depths never seen before and who cry on a given moon. Or of the -simply- oblivious to everything. And we are afraid of them, when they are reminded, for a fraction of the time, of our stolen distraction during the nighttime games of the night.

Celebration is devotion – an elaborate synthesis of all collective construction based on experience that unfolds in creative profusion. It is the act of celebrating that shows us ways of dealing with the intangible based on what we have. It presents us to the world as unfinished, awaiting inventions that betray everything that is intended to be infinite.

Surrounded by the aura of those who enter at the exact moment, due to the imminence of the end, we carry the body of the universe on a flat and thin plate, with much less of the dexterity of acrobats and convinced that we can, we don’t hesitate. We were intoxicated.

The gods are encouraged and much more than protecting, they are interested in being part of it. As fearless as they are, they flood and bury bodies – ours – because they don’t fit in so much. They consume everything that comes their way, because they celebrate without precedents. It’s always the first time. And even if they leave marks, they ignore them, because they’re talking about now.

Because we are small and fleeting, clay dust, we sing to make them happy and feed them to calm down for a few moments. In the meantime of eternity, we danced for the grown-ups, awakening in us some kind of force that would remove us from ordinary life. We created the floor of beauty.

The subject and the landscape

Vladimir Bartalini

When we say subject and landscape, we already assume a separation: on the one hand, the subject, on the other, the object. The subject, then, is the subjectum, the underlying, the one that underlies what lies, which rests on itself. Once the subject is established as the foundation on which everything rests, things, beings, the world, in short, everything else that is not that founding subject is an object.

The landscape would then be an object supported by a subject, dependent on him. It would also be an object upon which the subject exercises an action, an intervention; or an inert and neutral surface onto which the subject projects his feelings, values, and intentions. Eventually, the landscape would become an object of contemplation in loco, or on a canvas, in a photo, in a poem.

This interpretation would lead to the hasty reading of Fernando Pessoa’s phrase [1] in the Songbook’s preliminary note: “Every state of mind is a landscape”. If sad, the subject would represent his state of mind as a dead lake; if happy, like a sunny day. The landscape would then be nothing more than a mere projection of a subject’s feelings. However, a few lines ahead, after admitting the existence in us of “an inner space where the matter of our physical life is agitated”, the poet assumes that the consciousness of this inner space is simultaneous with that of the outside. We are then aware of two landscapes, one internal and the other external, that merge and interpenetrate, influencing each other: “our state of mind, whatever it may be, suffers a bit from the landscape we are seeing […] and the outer landscape also suffers from our state of mind”.

If, instead of separation, we want to refer to the inseparability between subject and landscape, it would be more appropriate to say subject-landscape, without conjunction, since it is neither a relation of independence nor of dependence between the terms: subject-landscape, with hyphen, since this diacritical sign not only unites but also modifies the value of the terms. We form and modify ourselves while we form and modify landscapes, and vice versa.

However, it is easier to admit this fusion in the written word than to convince ourselves, through the thought, that we and the landscape are one, although our psyche (or our soul) does not doubt this and even desires this union.

The landscape well embodies this desire to unite what is separate, or what thought (or certain way of thinking) separated when establishing and deepening the divorce between the subject and the vast world, a division that poets (of lines, light, colors, sounds, movement, matter, and words) and poet-thinkers intend to serve.

Man’s unity with the world occurs at the level of his own body and “appears in our desires, our evaluations, our landscape” [2]. “There are no men and, besides them, space. Space is not something that is opposed to man; it is not an external object or an inner experience” [3]. Simply, we are here.

When it comes to landscape, however, being here doesn’t mean being tied to a place. The landscape always implies a horizon, an beyond, an opening to the world and a constant slide that does not make a resort. The landscape, in this sense, is an exile to which we are led every time we travel. Perhaps this is what Agamben [4] refers to when he says that the landscape is inappropriate, as are the body and tongue.

The landscape is inappropriate not because it is distant, out of the reach of my hands but, on the contrary, because it is too close, because it is very intimate, because it constitutes me, just as my body constitutes me, without being able to get rid of it every time it imposes on me a need that was not based on my deliberation. My body then becomes foreign to me, preventing a clear distinction between “the voluntary and the involuntary, my own and the stranger, the conscious and the unconscious” [5]. The same is true in the poetic gesture, when the language, mastered and made foreign by the writer himself, becomes foreign to himself and dominates him.

The landscape is therefore familiar and strange to us at the same time, since, because it is so intimate, we surrender to it and lose ourselves in it.

The landscape inhabits us as a fluid, in a pervasive way (landscape painting proves this with the expansions of water and sky). But it is not just a medium, it is not confused with the “environment”. Because it constitutes us as subjects, it moves and moves us; it bewilders and welcomes; it rests; it endures; it lies.

The sea is an example of this fusion. It permeates the entire atmosphere, announces its presence in the mangroves that are still distant, along the extension of the sugarcane fields, salts the molasses. Brandy intoxicated the boy Joaquim Nabuco: “Farther away began the mangroves that reached the coast of Nazaré… During the day, due to the high heat, one would take a nap, breathing in the aroma, scattered everywhere, of the big pots in which honey was cooked” [6]. Since early childhood, it leaves marks that are definitely imposed on the experiences of adult men: “I have often crossed the ocean, but if I want to remind myself of it, I always have before my eyes, stopped instantly, the first wave that arose before me, green and transparent like an emerald screen, on a day when, crossing an extensive coconut grove behind the palhoças dos Jangadeiros, I found myself on the edge of the jangadeiros of the beach and I had the sudden, overwhelming revelation of the liquid and moving Earth… It was this wave, fixed on the most sensitive plate of my children’s Kodak, that became for me the eternal cliché of the sea” [7].

The presence of the sea is absolute, it merges bodies and things, it confuses the reason: “Old pavements clouded with tropical humidity. Stairs leading down to the black sand; with paper, waste. A silence like in the cities of the North. There are young people wearing carrion-colored jeans and white knitwear, clingy, dirty, walking along the balustrade — like Algerians condemned to death. Some farther away in the warm shade against other balustrades. And the sound of the sea, which doesn’t make you think…” [8].

In the Chinese tradition, one of the ways of saying landscape is shanshui, mountain and water, constancy and movement, resistance and subjection. But which is the acting subject: the mountain that opposes water, or the water that shapes it, which conforms to conformity? Water, even the most crystalline, blurs the distinctions. It is the universal solvent, and the sea, the source of water, is the resting place of beings in vertigo, who have “the destiny of flowing water” [9].

Immersed in the landscape, the subject no longer controls the action, but merely acquiesces, serenely. By startling the thought, the landscape, especially the aquatic landscape, modifies not only the subject but also his predicates: it even sweetens the ocean. “… This is how I drown my thoughts in this immensity: and my shipwreck is sweet in this sea”, say Leopardi’s verses in L’Infinito [10].

“It’s sweet to die at sea” [11], echoes Caymmi from the other side of the Atlantic.

[1] Fernando Pessoa. Poetic work. Organization, Introduction and Notes by Maria Aliete Galhoz. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Nova Aguilar S.A., 2005, p. 101.

[2] Maurice Merleau-Ponty. Phenomenology of perception, translated by Carlos Alberto Ribeiro de Moura. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1999, p. 16.

[3] Martin Heidegger. “Build, Inhabit, Think”. Translation by Marcia Sá Cavalcante Schuback. Rehearsals and conferences. Petrópolis: Editora Vozes; Bragança Paulista: Editora Universitária São Francisco, 2006, p. 136.

[4] George Agamben. The use of bodies. Translation by Selvino J. Assmann. São Paulo: Boitempo, 2018.

[5] Idem, p. 109.

[6] Joaquim Nabuco. “Massangana”, My Training, São Paulo: W.M. Jackson Inc. Editors, 1948, p. 228.

[7] Idem, p. 230.

[8] Pier Paolo Pasolini. “Seaside. White lights, crushed”. Poems. Translation by Maurício Santana Dias. São Paulo: Cosac Naify, 2015, p. 181.

[9] Gaston Bachelard. Water and dreams. Essay on the imagination of matter. Translation by Antonio de Pádua Danesi. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2002, pp. 6-7.

[10] Giacomo Leopardi, L’Infinito (1819-1821), translated by Haroldo de Campos.

[11] Dorival Caymmi, Fisherman’s Suite (1957).

BEYOND THE MARGINS

Artists

Cao Guimaraes

Christian Knepper

Elza Lima

Marcel Gautherot

Maureen Bisilliat

Pierre Verger

Ronney Alano

Walter Firmo

Collections

Moreira Salles Institute

Pierre Verger Foundation

Curatorship

Gabriel Gutierrez

Artistic Coordination

Deyla Rabelo

Gabriel Gutierrez

Expography

Claudia Afonso

Gabriel Gutierrez

Lighting

Calu Zabel

Visual Communication

Natalia Zapella

Research and Texts

Gabriel Gutierrez

Ubiratã Trindade

Vladimir Bartalini

montage

Diones Caldas

Fábio Nunes

Rafael Vasconcelos

Enlargements and impressions

Ailton Silva

Daniel Renault (Gicle Fine Art Print)

Lupa Studio

Supports

Speed Lab

Lupa Studio

Direction

Gabriel Gutierrez

Steering Assistance

Deyla Rabelo

Coordination of the Educational Program

Ubiratã Trindade

Educators

Alcenilton Reis Junior

Amanda Everton

Maeleide Moraes Lopes

Education Program Interns

Carlos Carvalho

Iago Aires

Jayde Reis

Lyssia Santos

Communication Coordination

Edízio Moura

Production Coordination

Nat Maciel

Producers

Pablo Adriano Silva Santos

Samara Regina

Financial Coordination

Ana Beatris Silva (In Account)

Financiero

Tayane Inojosa

Administrative

Ana Célia Freitas Santos

Reception

Adiel Lopes

Jaqueline Ponçadilha

Zeladoria

Fábio Rabelo

Kaciane Costa Marques

Luzineth Nascimento Rodrigues

Maintenance

Yves Motta (general supervision)

Gilvan Britto

Jozenilson Leal

security

Charles Rodrigues

Izaías Souza Silva

Raimundo Bastos

Raimundo Vilaca

President

Eduardo Bartolomeo

Executive Vice President of Sustainability

Maria Luiza de Oliveira Pinto e Paiva

Chairman of the Strategic Council

Maria Luiza de Oliveira Pinto e Paiva

Vice President of the Strategic Council

Flávia Constant

Chief Executive Officer

Hugo Barreto

warden

Rodrigo Lauria

Director

Luciana Gondim

Sponsorships and Projects Coordinator

Marize Mattos

Management and Governance Processes Manager

Gisela Rosa

Beyond the Margins

CCVM Catalogue