Exhibition

Renounce/Mobi

14 February to 24 June 2023

Tour Virtual

(…) And if it weren’t for those people who are there, maybe everything would already be ruined. (…)

Aloísio Magalhães, about São Luís and the directive for the preservation of historical heritage.

Just like those waters in which a drop of dye is spilled, which is enough to color the entire basin.

Jacques le Goff

Like everything under the sky, the city is divided between one side of light and the other of shade. Buildings and antennas are something in the morning rather than at dusk. At night, the streets return underground, in the sleep of some, when others wake up. In multidirectional dimensions, the city grows – layer upon layer, era upon era, party upon party, massacre upon massacre. As opposed to always complementary, things are created and destroyed. The north does not exist without the south, much less the heights, without the foundations that seek to reach China. The pitch on the pavements becomes thick, depending on the age of the avenues. Wrinkles accumulate, close to the curb. Everything is buried, but also banished. On the edge, the asphalt is not enough, because it does not follow (and does not want to achieve) the speed of the urgent founding of the new neighborhoods. It can even be said that it only pushes the land, together with those that belong to it, to the banks.

The shape is not foolish. The wall is not foolish. Street risk is not foolish. Houses aren’t foolish. The churches, the bridges, the squares, and the metallic horses that sleep in them, moving forward in an endless cramp, are not foolish. The drawing is a design and points outwards, in a project. No wonder, one of the first symbols for Greek cities was the trail of Apollo’s arrow in the sky, a projectile that determined the path to be traced. The inside, the outside and the property are delimited. At ground zero, the church rips, radiates, inaugurates. Matrix. The city is the place of religion because it is where the beggars are. It is religion itself, because it separates and divides. Let Nimrod say so. God lives in cities, but the devil! Not everything is so certain. Corners are an inaccurate game of chance. It’s like the tarot card that indeterminates: wheel of fortune, tower, hermit, car, emperor, lovers… hanged. It is, at the same time, the possible and the impossible. She is a mother and the executioner of destiny. It’s confusion.

It is the place of poetry, prose, and frenzy – public square – place of rally and trial, where the word makes crowds possible. And in the marches, shoulder to shoulder, hand, against the grain, elbows entwined. The gestures are raised in the air, an inspiration for those who raise their fists in the sky. The agitated university students establish an almost amorous dialogue with her. Between pride and contempt, students are caressed by the streets, squares, and amphitheaters and suppressed, with the right to sigh of relief when the banners are lowered and the night gives way to dispersion.

The city, par excellence, is the place of encounter and communication: on the white walls, a peek; on the poles, a mooring sign and magic; on the streets, trading floors; in the squares, a sermon. Party! What is celebrated in the city is urbanity itself, the congregation, the circus, the cycle, the fashion, the fantasy of the oppositional world. The ritual, as well as the sacrifice, is eternal. The clock punctually marks the guidelines of its pages. In them, we bump into what is coming and going far away, we schedule rendez-vous, we get stuck on the tracks. Nothing belongs — oh the carnival! In the blocks, we went alone and, when we got on the bus, we found it back home without wanting to find it. One against the other, we lowered our heads, for the detour… we prayed for solitude. We sneak our eyes, perpetuating what remains of fantasy, taking care not to be recognized outside of it, mortals that we are. The alleys, the alleys, the empty public stairs predict unsettling solitude. The work, every hour, the work. Everything is silent when you close the front door. The moment the lock clicks, the strange buzzing sound appears that sucks us in a few moments of vacuum. One day, we own the stages, in a few hours, completely anonymous, unchanged.

The city is a board of many pawns and a single king: each one in its own square. It’s an idea, an image, a persona, because it has a name. We don’t treat the city like numbers: city one, city two, city three. Not like the alphabet A, B, or C. There are no generic cities, and those that are intended are poor people! The city is pretending, because it knows before. It carries within itself something to come that does not yet exist, but is already present. Rather, the city is a political game. It gives birth to the abstract citizen, the model of the man for whom laws and prisons are intended… ostracism is always the maximum penalty. Object! The city isn’t for everyone, it never was. Get out there, Jeca! She is born exclusive. The Greek polis is where only those with names occupy a place in the sun. Urbes means round, like the orb, that is, the universal sphere that monarchs take over the world. It explodes and imposes the landscape. Nothing has changed, the city denies and snoops. And when he says it, he secretly denies it. Indecipherable, it rises like a protective sphinx that devours. In its riddle, power is a verb and a noun.

Ruin is your unavoidable and impermissible betrayal. In the cracks, pieces of field sprout, the domain of the natural, a remnant of the past over the past. Cheap, homeless, marginal. Rat, dirty dove! Riverfront, wolf mouth, flood. Cases. Inadmissible! And therefore, the latter are your offspring! They exist only in it and because of you. Saturn devoured its own children. The city is wild. She keeps the quality of a beast to herself. It does not admit competition. It only accepts docile bodies. But pretend! It only allows appearances. Animals are not such animals, within their limits: dogs on a leash, mutt cat, butcher meat. Perhaps, only those that fly, will keep up with the predator and prey in a hurry. Even where there is revolt, even what overflows and flows seems to be lost in the cynical concealment of climbing and descending sidewalks. Always stuck. We’re for the city. We migrated to the city; we gave up our own existence for the city, because we are a city. Creator and creature, in this place, have no distinction. Fake it! Like a stone of sacrifice, we give up our body, our name. To be all that, to swallow and excrete all things, from the city and its own, all that remains is to resign.

Resign

Photography is an urban language. It originated in the city and around the city. Like today’s major centers, it is the pinnacle of the simulacrum of the real. The first images in the history of photography are points of view of the city; not a spontaneous view, but rather forged by the equipment and the distance it provides to those who risk using it. We can say that the essence of photography and of the city become confused, in the proper sense of the things that merge together when they are so intertwined. Daguerre’s Boulevard du Temple, one of the first experiments in photography, is blatant. In that image, the only being that did not actually belong to the city was the one that remained stationary. Urban movement is essential for photography. Even when the object is natural, the view that covers it is urban. Without it, it wouldn’t be art. And then the movie theater.

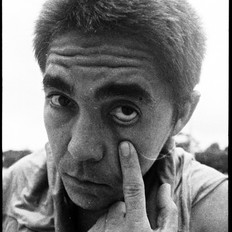

Mobi photographed São Luís and its agents. He didn’t make a landscape portrait, but instead captured the imbrications and tangent points. She captured herself as an inhabitant of the Amazon city disguised as a temperate city, slipping through the gaps. That is why, in view of the work, we see a suspended structure, which is summed up in a strange question mark, such as when we call someone we may have recognized on the streets – Mobi?

The adventures, the photo-journalistic function, the erratic gunshots, even the 3×4 of the document corroborate the mistake – everything is undated movement and fiction. Isn’t the city a fiction? Isn’t the city the object of imagination and representation? Simulacrum seems to be a preference of our time. How many images don’t resonate, like death masks directly in our atomized memory consisting of flashes? What part of the moment, of the real moment, is outside the frames governed by the photographer? For this reason, when faced with the image of the worn-out inscription: Resign, we wonder if this movement is not perpetual, and if: is it not the city in which we live, just a specter of every renounced vital power that resides in each of its citizens? The answer is yes and no, like walking on a trace that delimits a circle.

What did Mobi renounce? What do we renounce? Who resigns who?

The exhibition was designed as double-sided letters and proposes three narrative lines that can be mixed up. Mobi is the one who cuts the hill and distributes it. The first meaning is what we didactically call an official city. It is one that is easily visible to the eye, which we recognize quickly and which supposedly has historical value. The second would be the other way around, that is, what the city hides or what we would like to hide. It is this wild dimension that haunts us, the part of us that we bury, the animals that we kill. The third are spectator portraits, characters who experienced the São Luís portrayed, as we may be experiencing it today. They were caught in their retreat on things. They are spectators who, like us, are waiting for the riddle to unravel. While walking, it is with these characters that we exchange views, sometimes of complicity, sometimes of dislike.

Let each one organize their own range of bluffs. The images, as well as the cities, hold their mysteries. Above all, don’t compare yesterday with what was left or changed. Such an opportunity would be foolish. The world doesn’t fit in images, but it fits in cities. There is much more to it than meets the eye. Rather, the invitation is to deepen fiction, to trace new narratives based on urban inventions that allow recognition, so that we do not remain in our abdicated places.

¹ MAGALHAES, Aloisio. And Triunfo? The issue of cultural assets in Brazil. New Frontier — Pró-Memória. Rio de Janeiro, 1985.

² LE GOFF, Jacques. For the Love of Cities: Conversations with Jean Lebrun. UNESP. São Paulo, 2022.

³ SONTAG, Susan. About photography. Company of Letters. São Paulo, 2004.

City of Resignations

The territory builds relationships of coexistence with concrete structures that dialogue to materialize the abstractions involved in human construction. The complexity of urban events is a direct consequence of colonizing processes and runs up against current urban legislation, in a scenario of disconnections between rhetoric and practice. Territory is the matrix of all transformations in society and is a fundamental element for the formation of the identity and recognition of a particular group and its differences from another. Different forms of building and inhabiting coexist in urban space as formal and informal cities. The inequality fostered by modernity to affirm certain worthy individuals who are constituents of space created pluralities that mark the construction of the city in informal territories.

The formal city is the scenario that exists in urban legislation: a well-articulated system, with conventions and regulations that determine land use and occupation, favoring living conditions, infrastructure, accessibility, and safety in favor of the collective good. The informal city is built by marginalized social groups based on patterns of spontaneous settlements driven by their own need to live. Urban inequality is the historical consequence of favoring public policies and investments aimed at a single territorial area. Plural cities within the singular feed on each other by coexisting contiguously. Informality is constructed like Non-Being so that formality is based on Being.

The ruins of the city portray what is no longer wanted, the convergence of the past of formality that did not follow the path of modernity in search of continuous exclusion and the separation of what lives, coexists and survives in urban space. The existence of opposing cities living together contiguously is met with the construction of a collective space that everyone is entitled to. Collective living and living create a democratic system of dialogues, collaborations, and joint actions. The right to the city is essentially collective; equal access, mobility, participation, and choices in urban processes cannot be individual. The fragmentation of uses in the city promotes unequal relations and access that flow into segregation. The right to the city encompasses a plurality of demands from social movements, such as quality urban infrastructure, environmental balance, basic sanitation, diverse forms of mobility, and decent housing for the construction of a just society.

The right to the city and to housing are guaranteed by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and by Brazilian urban planning legislation. In the City Statute, established by Law 10,257/01, the right to sustainable cities encompasses “the right to urban land, housing, environmental sanitation, urban infrastructure, transportation and public services, work and leisure, for present and future generations” and also to democratic management through the participation of the population and representative associations (art. 2, item I). Law 11.124/05 ensures access to urbanized land and to decent and healthy housing. The right to the city is indivisible, non-transferable and all inhabitants of cities are its holders. However, even though it is a constitutional right, it is not part of reality. The rhetoric and practice of Brazilian urban planning are configured in a disconnected dance with opposing movements without conversion points.

It is the struggle of political minorities organized in social movements, such as residents’ associations, the homeless movement, and popular unions, that is capable of guaranteeing the inclusion of rights in the urban countryside for more egalitarian cities. Social movements that fight for the right to housing and land are building an essential struggle for urban justice. The right to housing is inseparable from the right to the city. Housing must be integrated with mobility, infrastructure, leisure and other components of urban life so that the participation of each citizen is not restricted to private property alone. The struggle for housing is part of the history of Brazilian social movements and are responsible for numerous collective achievements, but are historically criminalized and marginalized by the spatial segregation imposed by capitalist society.

Article 5 of the Federal Constitution states that “property shall fulfill its social function”. Every property, rural or urban, must be used in favor of the interests of society and not just of the owners. The social function imposes limits on property rights to ensure that its exercise is not harmful to the collective good. Buildings that do not fulfill their social function violate the legislation. The occupation of properties without a social function is the fulfilment of a duty provided for by law.

The formation and urban expansion of the Historic Center of São Luís are embedded in a largely colonial context that permeates its architecture and also the modes of occupation and production of the city. The urban process in São Luís took place in the midst of the slave period of colonial modernity. The colonizer’s vision permeates the historiography of the city, prioritizing a perspective of heritage appreciation over criticism of the social marginalization promoted during the urbanization of the Ludovicense historical area. The heritage of the Historic Center is analyzed in an appreciative and material way, ignoring the violence inherent to its construction. The discursive euphemisms of colonial modernity make visible the need to criticize the central area of the city as the starting point for urban, racial, and social inequality in São Luís.

In the second half of the 20th century, the Historic Center of São Luís became home to fewer and fewer affluent families and activities began to concentrate mainly on the commercial sectors. With the expansion of the city, the opening and paving of new public roads, such as Avenida Getúlio Vargas, allowed the transfer of the high-income population to areas increasingly remote from the center. The devaluation and marginalization of this area became increasingly evident; the social image of an environment of aristocratic families and refinement collapsed as the poorest population occupied these spaces in greater numbers.

In this context of segregation, the struggles of social movements for urban rights gained strength and took place in the Historic Center. The basis of modern processes in the city of Ludovicense was built on the pillars of coloniality, reinforcing exclusions in the city, demarcating the formal and informal city and its proper inhabitants. The island of São Luís presents numerous urban problems that impose veiled segregations and marginalize the population to peripheral and undervalued regions, in order to ensure and demarcate the difference between classes. Social movements, responsible for all the achievements in favor of a more collective city, in a scenario with more than 60 years of struggle, are still resisting.

Urban space is built on sacrifices. The formal city renounces informality and what does not align with the logic of modernity. Renounce the ruins. Renounce animals in matter and in the imaginary. Waiver of collective uses to promote exclusivity. The choices in urban construction renounce the Other, the one that was built to be the informal as the foundation of those who live in formality. The ideas out of place and the place out of ideas renounce the city for housing, promoting inhabitants who do not live there. Residents who don’t live. They live in the coming and going of daily sacrifices of mobility that exploits segregation. Individuals who resist not renouncing their rights coexist in the city, even if it renounces them. All rights permeate urban territory, because the city is the scene of all revolutions. Resignations between formal and informal cities build a place that does not belong to everyone and that also does not belong to anyone, making it just a city of renunciations.

Larissa Anchieta

São Luís, December 2022.

Biography

June 1953

Luiz Gonzaga Araújo Frazão – Mobi – son of the Ceará weaver and teacher Teresa Oliveira Araújo and the merchant Benedito Frazão, was born in Ipixuna, currently known as São Luiz Gonzaga.

1969

He moves to São Luís do Maranhão.

1978

He began his professional work as a photographer after a brief training in Fortaleza.

1982

He held his first solo exhibition Facets of the Island, reading Ferreira Gullar’s Dirty Poem, at the Alliance Français gallery in São Luís.

February 1985

He holds the solo exhibition Aspects of the Island at the Newton Pavão art gallery of the Joaquim Nabuco Foundation, located on Rua do Giz 49 in the Praia Grande neighborhood. Soon after, take the same exhibition to the PDT Conference Hall in São Luís, to the São Lourenço Cultural Center, in the city of Curitiba, Paraná, and to the Mondego`s Bar, in the neighborhood of Fátima in São Luís

The 12th Maranhão Folklore Week photo contest won, sponsored by the Department of Culture of the State of Maranhão, together with the Domingos Vieira Filho Popular Culture Center, with the series of photographs depicting the handmade treatment of leather to make instruments used in manifestations of popular culture.

January 1986

Mobi is part of the Renovação ticket, a candidate for the board of directors of the Professional Association of Photographers of the State of Maranhão, and proposes to hold the position of director of outreach and promotion.

March 1986

The Renewal ticket is elected and Mobi assumes the position of promotion director. The Professional Association of Photographers of the State of Maranhão was founded in 1976 and deactivated years later. The election of the new ticket brought hope of activating and organizing the class.

April 1986

His third exhibition, Fragments of the Earth, opens at Galeria Eney Santana, bringing to the public a critical view of Ludovicense society.

June 1986

It exhibits Fragments of the Earth at the Eney Santana Gallery, attached to the Arthur Azevedo Theater.

September 1986

It organizes, together with Paulo Socha, the 1st Collective Exhibition of Photographers from Maranhão.

1987

He takes the position of photography professor at the Maranhão Society for the Defense of Human Rights.

June 1987

He holds his fourth photographic exhibition at Galeria Eney Santana, entitled Foto Pin, following the same narrative line: the city, human beings, and everyday life.

August 1987

She is part of the group of Ludovicense photographers from the 6th National Photography Week, in Ouro Preto, where she participates in the workshops Street Photography, the Act of Photographing, and Photography and Cinema.

1988

He holds the photographic exhibition Negro Trabalho at Galeria Eney Santana.

1989

He holds the photographic exhibition Experiencing Barreirinhas, by the Bank of Brazil, in the honored municipality itself.

April 1989

He won the Gaudêncio Cunha Photography Prize with the work The Little Rocket Man.

June 1989

He taught the first Dynamic Photography Course sponsored by the city of Barreirinhas.

November 1989

He coordinates, with Luís da Paz, the II Photography Exhibition, bringing to the debate the importance of the photographer profession for society.

June 1990

She will be exhibiting at the 1st Photography Week at the Odylo Costa Filho Creativity Center – Transition or Transaction Exhibition.

August 1990

He held the III Collective Photography Exhibition.

June 1991

The exhibition Lagoa da Jansen Death and Life opens at the Odylo Costa Filho Creativity Center.

August 1991

He exhibited during the II Photography Week, at the Odylo Costa Filho Creativity Center, alongside photographers from Maranhão, such as Ribamar Alves.

April 1992

She received an honorable mention in the Filhos da Precição photo contest, sponsored by the State Secretariat for Culture and the Brazilian Center for Childhood and Adolescence.

October 1993

He marries Raimunda Pinheiro de Souza, who goes on to sign Raimunda Pinheiro de Souza Frazão.

September 1994

With Raimundinha, Mobi founded the Regional Ecological Movement for Health with Art – MOVERSARTE, with a big party at his residence. The project was responsible for social, environmental, and cultural initiatives aimed at residents of São José dos Índios. During its existence, it worked in partnership with non-governmental organizations to demand from public agencies for better living conditions for the population, for the preservation of the environment, promoting vocational courses and cultural actions. Artists from Maranhão such as Dona Teté, Sandra Cordeiro, Rosa Reis, Mestre Felipe, among others, collaborated with the movement.

1996

He holds the São Luís exhibition in Photos and Poems at the Philatelic Post Office.

June 1999

MOVERSARTE presents the exhibition Ovo no (Backyard) Nosso, with photographs by Mobi, at LABORARTE.

March 2007

Mobi dies the victim of a car accident.

RESIGN/MOBI

Curatorship

Gabriel Gutierrez

Artistic Coordination

Deyla Rabelo

Gabriel Gutierrez

Expography

Gabriel Gutierrez

Raimundo Tavares

Texts and research

Deyla Rabelo

Edízio Moura

Gabriel Gutierrez

Larissa Anchieta

Ubiratã Trindade

Lighting

Calu Zabel

Karine Spuri

Mobi Documentary

Beto Matuck

Visual Communication

Fábio Prata, Flávia Nalon (PS.2)

Text Review

Ana Cíntia Guazzelli

Digitization of the Photographic Collection

Adson Carvalho

printout

Daniel Renault (Giclê Fine Art)

Mobi Collection

Edu Cordeiro (responsible)

Photo curator

(IFMA – São Luís Campus/Historical Center)

Executive Production

Maria Silvestre, Marcelo Comparini (MC²)

production

Alex de Oliveira

Pablo Adriano

Samara Regina

montage

Diones Caldas

Fábio Nunes Pereira

Marlyson Nunes

Nebraska Diamond

Rafael Vasconcelos

Renan José

CENOTECHNICS

Painting

Gilvan Brito

Locksmiths

José de Souza Cantanhede

Electric

Jozenilson Leal

joinery

Dyoene Frazão Ribeiro

Edson Diniz Moraes

Nerilton Fontoura Barbosa

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Adson Carvalho

Edu Cordeiro

IFMA – São Luís Campus – Historic Center

Raimunda Frazão

Direction

Gabriel Gutierrez

Steering Assistance

Deyla Rabelo

Coordination of the Educational Program

Ubiratã Trindade

Educators

Alcenilton Reis Junior

Amanda Everton

Maeleide Moraes Lopes

Education Program Interns

Carlos Carvalho

Iago Aires

Jayde Reis

Lyssia Santos

Communication Coordination

Edízio Moura

Design

Ana Waléria

Production Coordination

Alex de Oliveira

Producers

Pablo Adriano Silva Santos

Samara Regina

Financial Coordination

Ana Beatris Silva (In Account)

Financiero

Tayane Inojosa

Administrative

Ana Célia Freitas Santos

Reception

Adiel Lopes

Jaqueline Ponçadilha

Zeladoria

Fábio Rabelo

Kaciane Costa Marques

Luzineth Nascimento Rodrigues

Maintenance

Yves Motta (general supervision)

Gilvan Britto

Jozenilson Leal

security

Charles Rodrigues

Izaías Souza Silva

Raimundo Bastos

Raimundo Vilaca

President

Eduardo Bartolomeo

Executive Vice President of Sustainability

Maria Luiza de Oliveira Pinto e Paiva