Exhibition

Maranhão: Indigenous Land

26 September 2023 to 17 February 2024

The Ministry of Culture, Vale and Vale Maranhão Cultural Center present the exhibition Maranhão: Indigenous Land. The exhibition provides an overview of the indigenous peoples of Maranhão through their traditional material cultures, worldviews, territories, and languages. Rituals, myths and oral heritages related to the production on display are discussed, as well as aspects of the daily life of the indigenous peoples Awa Guajá, Canela Rankokamekra, Canela Apanyekra, Gaviao Kykatejê, Gavião Pykopjê, Ka’apor, Guajajara Tenentehar, Krikati, Tembé, Krepun Katejê, Akroá Gamella, Kreniê, Tremembé, Anapuru Muypurá, Tupinambá and Warao.

Virtual Tour

This is how we continue to be indigenous in the bodies we have and in the culture that enlightens and guides us. But of course, the indigenous people who resisted the overthrow are much more indigenous. That’s why I spent so much time with them. Now, I invite you to shake my hand and come with me to visit your villages again. Have a good trip.

Darcy Ribeiro

Maranhão: Indigenous Land is the vindication of a fact. The two dots of the sentence can be replaced by the verb ‘to be’, in the present indicative: it is. Maranhão is an Indigenous Land! As a manifesto, the sentence unites two instances that, although they are part of the same political device for the constitution of the territory, remain strategically separated. By affirming them together, the State’s impositions on that same territory are suspended, in an exercise to reverse the historical denial of the rights due to native peoples. The whole is the part, not the other way around. The statement is radical, because indigeneity thrives at the root of things. Those who, in confrontation, take the side of those who see life as a creation resist lethal alienation: I am indigenous because I produce my existence in a radical way.

It is the other way around that the imposed structures are dismantled. Behind the fictional appearance, we arrive at the actual origins. The resumption requires the unveiling of the original meanings, in addition to the grounded story. Overcoming hegemonic logic, asking things the other way around and filling in the gaps based on the hegemonic discursive material itself, let’s say cool, calls into question the moral/mortal values of the white colonizer. Affirming that the state is an Indigenous Land signals the exact moment of the colonial crime that establishes two opposing ways of being in the world; two different understandings about the land; two incompatible ways of defining and living the territory: the denial of the dominator – owner; and the affirmation of the dominated – property. This was and remains the nation-building device. It is impossible not to agree that the lands, once home to diverse populations with their own languages, cultures and agencies, were stolen for the sake of a civilisational idea. We know very well that a war was waged over 500 years ago, because of its presence over the territory in question, and that it remains today. The alien denies it, the indigenous affirms.

Maranhão is an maiden name. It was determined by the one who took the omen of the gods to justify and consecrate his wills. It is the denomination that gives the political outline to the state, establishes borders, houses the segmented economy – tourism, heritage and taxidermized geography: regular topography, capital: São Luís. Finally, Maranhão designates the set of laws that make it exist as a Brazilian state, for Brazilians (?) – abstraction about everything that is palpable to be abstracted, removed, considered in isolation. Indigenous Land is the name given, also by those who inaugurated, to the portion of minority land destined to the populations that once named and delimited their own territory. Uniting the nomenclatures stems from the desire to take the inauguration power for oneself and thus to take the place of the one who gives the name, that is, the place of autonomy. It’s not just wanting more, but rather guaranteeing the right to want.

Autonomy is the main characteristic of indigenous peoples. Autonomy means giving one’s name, creating one’s own laws, producing one’s own existence. This is the meaning of indigenous ownership. It is opposed by the white logic of alienating production from means of life. The two differences are reflected in the territory: the first, in an integrative, communal, public relationship; the second, in a disarticulating, alienating and private movement.

Never in history have indigenous peoples renounced the control of producing their own food, their own medicine, their clothing, their language, their own paths; of being their own in the relationship they build with the territory. When entire populations were displaced or chose death over enslavement, they were preserving the active place of their agency in the world. How to withstand such strong roots? Such freedom is unacceptable for those who do not do it with their own hands, as well as for those who, for free, cut them off and throw them at them. Hence, the genocide. However, the indigenous body – whole body, territory body, root body – resists with its feet stuck on the ground. All this while the world presents itself as a crowd of chickens cut their throats, chasing their own desperation, horror movie.

The collection

In order for the visitor to achieve the smallest experience of being indigenous, it was decided to present the elements that can mediate the intersection between worlds, and that, in the eyes of the beholder, translate into forms, colors and uses, the way of seeing those who produced them. My eyes are your eyes. The human being is devoid of everything, and for this reason he needs to delimit his contours by means of what he produces. Deprived, they organize how to deal with what surrounds them, supplying what is lacking, in practice.

The fascination of those who lick objects with their eyes will come from what they feel: I like the earth. Every aspect of material culture is the result of the complex relationships that the individual establishes between himself and the community, between the inside and outside, between the body and the territory. Time was responsible for decanting the aesthetics of each people, a proposition intertwined with nuances, appropriations, reliefs, and meanings. From baskets to clothing, from ritual masks to instruments of war and fishing, the delicate dialogue between the pleasure of creation and being a territory is presented. Each account, plot, and form has a specific use, determined by the exact location, for the exact location. You don’t create a need. Art for art’s sake? Far from it!

It’s not about art, because they were produced in contrast to the Western, Eurocentric, white, colonizing, and universalist cultural system. They are not art, either, because they respond to the precise and necessary use. Furthermore, far from the signed inheritance, they are bequeathed by the collective authorship that makes up what we commonly call ancestry. They are not given to the dollar, the pieces are the result of the vision defined by its own cultural agency. Things speak in their native languages and through them they are able to transmit, to those who know nothing, a portion of their depth, in their wide reach. Whoever listens to the plays will hear words they don’t understand; but just like when listening to a foreign language, through the forms and gestures, through the approximation and modulation, they will feel some meaning resonate with them.

The relationship with the earth and with everything it contains is present in every object, not in a naive way, because it is imbued with the responsibility that the freedom to create has over the ongoing war. There is pleasure in every bead stuck in the thread and against pleasure, nothing can. Every bill screams: I wish! The techniques, forms, and symbols are determined by the land on which the cohesion of the collective’s basal culture is built. It is on these roots that everything else is established. These are the weapons that are presented. Indigenous objects contain the most refined synthesis of the intertwined relations of the cultural order: politics, religion, language, territory, etc.

What is presented is not an index collection, but rather pieces grouped based on the sensitive, on what enchanted the eye, on the beauty of the workmanship, on the sale agreement, on what was brought through the hands of the peoples, on what was sought as representative for a greater understanding of the indigenous world. The collection is the fruit of a flow. Maranhão: Indigenous Land, as well as Brazil: Indigenous Land, are proposed as statements regarding the presence of the peoples that are intended to be erased. Yeah, here they are! They present themselves with joy, poetry, beauty, meaning and strength. To appreciate what you see is to let yourself be indigenized, to be at the side of those who, alive, have roots that belong to the earth.

Gabriel Gutierrez

São Luís, July 2023.

The ancient heritage of the ancient peoples in Maranhão

From the distant past, in the Lowlands area of South America, especially the vast territory of the Amazon biome (including much of the current state of Maranhão), human populations have lived that have left marks and vestiges in landscapes and soil, showing great diversity and dynamics in management, survival strategies and adaptations to different environmental contexts over time.

Their knowledge and knowledge were transmitted in successive generations through a strong bond of traditions, in which experiences in society based on a sense of community and the oral transmission of cultural practices stood out. These peoples were deeply familiar with nature, exploring ecosystems in search of food and developing their own way of life, which was defined by technical, ritualistic and sacred choices, also reflected in the differentiated treatment given to the dead and the production of objects characteristic of each society and cultural period.

In Maranhão, the oldest inhabitants recorded by archaeological research to date were hunter-gatherer populations in the continental area. These groups maintained themselves through gathering and hunting, specializing in the manufacture of stone artifacts, bifaces and chips, hand axes, as well as arrowheads and spears, generally in flint, some of which were of great technological refinement, as observed in the process of chipping and finishing pieces found in the Amazon area of the state. The dates obtained were made by analyzing the remains of coal in campfire spots found during surveys up to two meters deep, placing the existence of these groups in a time range between seven and nine thousand years before the present.

Other populations also stood out in the exploration of coastal environments, especially at the interfaces of mangroves, sandbanks and paleodrainage channels, where they built artificial mounds from the accumulation of food remains from fishing; in the collection of molluscs and daily activities, a material culture derived from the exploration of resources, in addition to the reuse of bivalve shells, chips, artifacts, bone ornaments and stone axes. These sites retained the Tupi designation: sambaqui (a word that means heap of shells), encompassing an extensive temporal section, in addition to a special concern for the deposition of the dead, generally in a fetal position. The sambaquis on the coast of Maranhão and Pará also show the occurrence of a ceramic whose clay preparation involved the remains of crushed shells, a cultural trait different from the rest of the country.

Subsequently, the experimentation and management of plant species was also consolidated in the strategic distribution of some species, permeating native forests. The practice of more systematic agriculture of cassava, corn and peanut assumed importance in the food base, which, combined with the very long tradition of fishing, hunting and gathering, made it possible to increase population numbers. In parallel, new types of settlements emerged – although this was not a rule – where people lived in large communal houses, divided into subgroups of families, according to the mythical affiliation of their ancestors. These traditional ways of life lasted for a long period, characterized by great linguistic and cultural diversity, in addition to the formation of territories based on associations, control and war, establishing areas of interface and influence between the different groups. Ceramics, utility or ritual, were of great importance in the daily activities associated with a lithic industry, with refinement in the production of polished axes, pestles and mortars, made from the selection of suitable rocks and worked by chipping and abrasion on the banks of rivers and rock outcrops.

In the floodplain areas surrounding the Golfão Maranhense, between the years 250 and 1000 of the Common Era, ceramic societies, builders of stilts inside lakes, specialized in the exploration of these environments. They settled in villages of communal houses built on Amazonian hardwood pilotis and produced a rich and varied ceramic of their own appearance, with human and animal inserts, as well as various containers with varying dimensions and decorative painting elaborated on the inner side, in addition to anthropomorphic and Muiraquitan figurines. A part of this material repertoire suggests an approach to the rich and mysterious shamanic universe of the Amazonian peoples.

In the territories that comprise the Maranhão savanna, a region with higher topographic altitudes, varied vegetation and large drainage systems, peoples before contact left traces in sandstone walls, caves and paving slabs. Complex panels of engravings illustrate the symbolic universe and individual and collective expressions embedded in the landscape, reaffirming their temporal permanence as an expression of ancestry, testimony and support for memories of great importance due to their interactions with worldviews and rites of passage. There are also rarer examples of rock art with paintings on the borders of the municipalities of São Domingos and Tuntum, depictions of graphics in ochre, red and yellow colors, of zoomorphic (characterizing animals) and anthropomorphic (human form) motifs, in the Élida cave.

Starting in the middle of the Christian Era, the expansion of the Tupi-Guarani peoples, originating from the southwestern Amazon, took place. There are several hypotheses about the migration routes of these groups. The discovery of ceramic vessels on the island of São Luís, based on carbon 14 carbon dating, marked the passage of 250 years before the arrival of Cabral. This set of circular containers had reinforced red borders, internally decorated in black on a white background, with complex designs. Because the paint is soluble in water, combined with the fact that other smaller vessels accompanied the set were found, the most probable hypothesis was formulated to be a ceramic used in ritual burial practices. The morphological and decorative characteristics of the pieces refer to the Tupi-Guarani archaeological tradition, already located in the Baixada Maranhense and in the central area of the state. These groups are the historical ancestors of the Tupinambá, described by the first European chroniclers on São Luís Island in the 17th century.

During the European expansion to the West, the Tupinambá peoples dominated much of the Atlantic coast of South America, being the most described by travelers and religious, although based on a Eurocentric vision inserted in the process of friction that characterized the colonization and annihilation of a large part of these populations. The Tupinambarana society was distributed in the region, in 27 villages on the island of Maranhão, in addition to many others in Tapuitapera and Cumã. They were highly mobile warrior societies and inhabited villages of four communal houses around a central courtyard, surrounded by palisades. War and revenge were characteristic features of these groups, in addition to the ritualistic practices of ingesting their enemies as a way of recovering and avenging the forces of their ancestors. They had in-depth knowledge about nature and the stars, in addition to having a rich and diversified pantheon of myths and legends that underpinned their conceptions of the world, especially the migration of the souls of warriors in search of the ‘Land without Evils’, their vision of paradise.

Subsequently, the colonizing process of European expansion was brutal and annihilated, enslaved, and tried to erase the cultural values of large numbers of these original groups and populations. However, their tenacious resistance, for almost five centuries, enabled the survival of some ethnic groups and their descendants, who currently imprint on the features of our people the hallmarks of generations of the heroic landlords that trodden the territory of Maranhão.

Deusdedit Carneiro Leite Filho

Archaeologist. CPHNA-MA

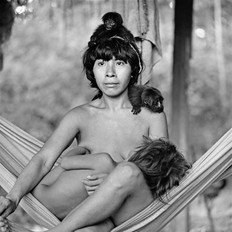

Awa Guajá

Arrows to live and fight for the right to be people: awá. A link between the Awá and the Karawara, those people from heaven who teach singing to people from the forest. Singing takes the night and brings the Awá to heaven and the Karawara to the earth. Beings that bring the warm breath that heals children, women and men who insist on walking, wata, along their paths under the green canopy of the last remnants of the Maranhão Amazon. “Where did the hunt go? Over there, over here? In the forest plundered by the Karai?” Singing is a guide and arrows guarantee the right to sing.

The non-indigenous people, Karai, made themselves known by their noise. Spoken memory, now also written, of children playing in the stream and the never-before-heard melody of firearms getting closer and closer. A child died while the Karai fired their instruments at entire families who were fleeing in pieces. “There are no Indians in the Greater Carajás region”, and now there were none.

Along paths opened by the feet of Awá and other people, their Hakwaha, they follow. The arrow that the boy learned to make with his father hit leaves, killed calango and little bird. Now, like an awá tea, real people make arrows, wy’ya, which kill monkeys and guariba, and arrows from taboca, kihia, that kill tapir, deer, jawbone, and caititu. The Awá take care of the game cub that survived the war. Milk that feeds Awá and Cotiazinha, directly from the breast or into the syringe, reinforces the bonding fluid.

In another foray into the forest to remove the reeds (Gynerium sagittatum) that will form the arrowheads, the Awá woman spots the honey, Haira, that will form her children. Singers and connoisseurs of a variety of honeys and their makers who continue to resist the insatiable karai. After making their weapons sing against the Awá – some of the survivors carry pieces of contact inside their bodies – the Karai used other weapons to tear down the forest and silence the various types of people who lived there.

After selling the pieces of wood, they set fire and brought their own animals that graze dying on the ground of burnt grass and babassu palm trees. On paper, the karai who owned the land were forged. Rupture of the paths formed by so many people. Four discontinuous Indigenous Lands and, apart from the official maps, only landlords and the hunger of those other people who started to eat land and continued to tear up the body and territory of the Awá. The Karai, with their dogs, their knives, their shotguns, and their machines that cut down trees to make way for the noisy earth-eater. They also opened holes that can be seen by their satellites; it dyed people and rivers a red that is not that of annatto. The earth-eater meanders rivers that are no longer black, narrow and full of fish as they used to be.

It passes through the Carajás Railroad countless times, day and night. The bottom of the river and the forest floor shake, the hunt is amazed, it goes far away. The Awá are also amazed by the diseases that spread and carry children and the elderly. The Awá’s roads now lead to barbed wire from farms, to dirt and railroads, to bars, schools, and churches.

In the villages created to house the Awá Guajá survivors, amidst the dusty heat, they continue to make their arrows, rods carefully pierced by the hands and feet of the man Awá, Awá Wanihã, stretched in the fire before the eyes of those who make calculations unknown to the Karai. The laminated tip of the taboca (Guadua glomerata), carefully sharpened with the aid of a machete or a caititu tooth, is joined to the rod by the tucum fiber rope (Astrocaryum), a line prepared and woven by the agile hands and feet of the Awá woman, awá wahya. The black resin of anani (Symphonia globulifera), iratya, is rubbed on the tucum rope that holds all the components of the arrows firm, unbreakable support. At the end of the rod, two peacock, vulture or mutum feathers are attached, a curvature that stabilizes and establishes the precision of the arrow that will be fired by the great bow, irapa, made of the foot of ipê found fallen in the middle of the forest.

The arrow with its tip and hook, Ita’iña, slaughters guars and monkeys in the wars that take place in the treetops. Desire and anger in the blood-poison, Hawy, from the fighters where the arrowheads were smeared. “Where did the hunt go?” In the song, in the dream, on the trail, the hunt is revealed and the arrow is ready to hit, with certainty, the prey that will feed the hunter, his hapihiara and other arrows.

Kwarahy Mehe, it’s summer and the Awá can now go to heaven, Awá oho Iwape, but it is necessary to make more arrows. Protection against attempts by the Karai to continue to advance over the bodies and paths of the Awá. The singing takes on the night and swallows the clinging noise of the earth-eater. Men adorned with necklaces and armbands made of ruby seeds and toucan feathers, with vulture king feathers surrounding their bodies, held by the white pitch that spreads the good smell while each karawara dances among women in tucum fiber skirts. They sing the songs that sustain their husbands in heaven and guide them back to the tocaia.

The earth-eating scream does not let the Awá forget that they are under attack, just as the river does not forget every grain of earth moved by the incessant trembling of articulated appendages. Amidst stories about the end of different worlds, the Awá sing and make arrows so that they can protect themselves from the unbridled appetite of those who insist on annihilating worlds different from the world that they miserably create for themselves.

Flavia Berto

São Luís, July 2023.

Krikati

The Krikati, also called themselves Krĩcatijê, carry a deep meaning in their designation. Krĩcatijê translates as ‘those from the big village’, an expression that reflects the importance and centrality of their community. Curiously, this denomination is shared by the other Timbira groups, establishing a cultural connection within the indigenous context. In contrast, the Pukopjê neighbors refer to the Krikati as Põcatêgê, which means ‘the ones who dominate Chapada’, possibly highlighting geographical or territorial aspects.

The Krikati language belongs to the Jê family, with its root in the Macro-Jê trunk and specifically included in the Timbira Oriental subgroup. Also known as Krikati-Mirim or Gavião do Maranhão, this language reveals its own characteristics, including a complex grammatical system and rich oral tradition. The Krikati have a deep connection with their traditional language, an intrinsic part of their cultural identity. The contact with the surrounding society led to the fluency of some members of the community also in Portuguese, an essential domain for intercultural communication.

The territory of the Krikati is the Krikati Indigenous Land, an area demarcated in 1992 that covers an area of approximately 159,169 hectares. This region is located in the eastern part of the state of Maranhão, in the municipalities of Montes Altos and Sítio Novo. A notable feature of the territory is the presence of rivers and streams from the Tocantins and Pindaré/Mearim river basins, which play a crucial role in the life of the Krikati. TI Krikati is the birthplace of two main villages, São José (the largest and oldest) and Raiz (founded after the demarcation), while a third village, Cocal, brings together Guajajara individuals married to Krikati women.

Regarding the population of the Krikati people, it is difficult to determine the exact number of individuals, as there have been variations over time due to factors such as birth, migration and other demographic aspects. However, according to data from the National Indian Foundation (Funai), the Krikati population is estimated at around 1,300 people.

Due to the common reference in historical sources between the Krikati and the Pukopjê, at the beginning of the 19th century, the total population of the two groups was estimated by Paula Ribeiro at approximately 2,000 indigenous people. In 1919, a census by the Indian Protection Service (SPI) indicated a population of 273 indigenous people distributed between the villages of Engenho Novo and Canto da Aldeia. It was not until the 1960s that the populations of the two groups began to be indicated separately.

Source:

LADEIRA, Maria Elisa; AZANHA, Gilberto. Krikati. Socio-Environmental Institute, 2018. Available at: < https://pib.socioambiental.org/pt/Povo:Krikatí >. Accessed on: August 07, 2023.

They - the Krikati women

Ka'apor

“Pirambir said that Mair was a real capor […] who would live far away, where the sun descends to the Earth.

Does the sky touch the Earth?

Exactly. It’s in Iwi Pita, where Mair lives. The sun rises near your house, rises to the sky… and descends there.

And how do you get close to Mair’s house?

The sun is a man, it’s like a man. When he lies down, he walks back, underneath us. Down there are forests, there are rivers, it’s a world just like ours.

Who did it?

I don’t know, Mair did it. He made it all beautiful and put a headdress on his

head.”

(HUXLEY, 1963, p.244)

KA’APOR FEATHER ORNAMENTS

The above fragment is a conversation between the English anthropologist Francis Huxley and Ka’apor Antonio-Hur in the 1950s, a period in which the ethnologist lived with this indigenous community located in the north of Maranhão, precisely on lands bordering the Gurupi (to the north) and Turiaçu (to the south) rivers.

Antonio-Hur, impressed and discredited by Huxley’s geographical notions, decides to tell a myth that portrays, among several aspects, the Ka’apor’s understanding of the limits of heaven and earth. The story tells how Pirambir — an ancient indigenous person — discovered the ‘end of the world’ (iwi pita) and the creative hero Mair (or Maíra):

One day, by chance, Pirambir found himself in a place where the entire landscape was gray and the trees burned. The only color I saw was that of the birds that lived there: macaws, parrots, japus, and other birds. At one point, he saw a village. As he got closer, he heard a grinding sound and concluded that someone was giving peanuts to the macaws. Later, Pirambir revealed to his colleagues in the village that he was Ara-yar — the owner of the macaws — a handsome man who wore a headdress, a feather necklace around his neck, and other feather ornaments

all over his body.

This myth associates feather ornaments with the figure of the creative deity, the great hero Ka’apor, Mair. Mair is the sun itself, the light, the ideal model to be followed by every Ka’apor individual. The headdress or diadem is his crown and the symbol of creation, made with the feathers and feathers of the birds mentioned in the myth, symbolising that Mair has all the virtues of these animals, just like any other Ka’apor who wears it. Fire symbolizes destruction and, at the same time, renewal, elements necessary in the life cycle. All these signs enhance and give meaning to the productions of this ethnic group.

Ka’apor plumaria is a form of connection with the spiritual world. The indigenous are produced to appear to their divinities; to be recognized by them and to establish alliances, in order to keep life in balance and guarantee prosperity for the villages. This connection justifies the reason why Mair is so referenced in mythology: he is a model to be followed; his attributes are directly connected to his form and appearance.

The body is the field of political, aesthetic, and cosmological elaboration for these people. Feather ornaments and other types of ornamentation, in addition to being understood as creative elaborations that materialize the ideals and aesthetic criteria of the Ka’apor, are also elements of agency, which respond to the demands of social and spiritual life.

When a Ka’apor uses the yellow feathers of the Japu’s tail — a bird that is highly respected and worshiped for its singing and weaving skills — to produce the headdress of the sun, it does so both for the beauty of the feathers and for the attributes that the animal can add to social life. The headdress is the materialization of the bird’s spirit. Its new form will allow the individual with the wearer to inherit their virtues and become an excellent singer at major ceremonies or a great weaver for the community, for example.

The ornaments produced stand out for the flexibility and lightness with which they sit on the body, for their subtle color contrasts and for the shapes and motifs present, all made with great precision and refinement. In addition to the headdress or headband (akangatar, worn only by adults, with rare exceptions), there are headboards (akang-putir), combs (kiwauputir), tembetás (paddy-pee, restricted to men), collar-whistle (awa-tukaniwar, for use restricted to adult men, in ceremonies), necklaces for women (tukaniwar), earrings (nambi-porã), floral bracelets (diwa-kuawhar), armbands (diwa-kuawhar), armbands for women simple bracelets (iapu-ruwai-diwá), bracelets (arará, also used as anklets), skirt ornaments (macaw, for women’s use), belts and sling.

The elaboration of plumary adornments follows the logic of form-function. All aesthetic and technical choices respond to the demands of use, taking up the values and signs that make up Ka’apor cosmology. The geometric shapes present in the earrings and the figures of birds in the lip ornaments and pendants of the necklaces are obtained through a process of gluing feathers on flexible bases (fabric, bark, dry leaf, etc.), as in a mosaic.

These techniques respond precisely not only to the wishes of those who produce the artifact, but to the needs of everyday and ceremonial use. From the Ka’apor cosmological perspective, a plumary ornament has the shape of a bird, not because it is a representation, but because the bird itself is materialized in a new form.

Alcenilton Reis Junior and Erick Ernani

São Luís, August 2023.

4 The full narrative of the Pirambir myth can be found in the book Lovable Savages (1963, p.240-244), by Francis Huxley.

References

CESARINO, Pedro. The Politics of Impermanence of the Amerindian Arts. I Virtual Symposium on Indigenous Art in Communication. May 2020. Available at: < https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Suvz26zBC9U > Accessed on July 12, 2023.

LAGROU, Els. Indigenous art in Brazil: Agency, Alterity, and Relationship. Belo Horizonte, Editora C/Arte, 2009

.

HUXLEY, Francis. Lovable savages: an anthropology among the Urubu Indians of Brazil. Trad. Japi Freire. Vol. 316. São Paulo: Companhia Editora Nacional, 1963

.

RIBEIRO, Berta G; RIBEIRO, Darcy. The plumary art of the Ka’apor Indians. Rio de Janeiro: Brazilian Civilization, 1957

.

Guajajara

MOQUEADO PARTY

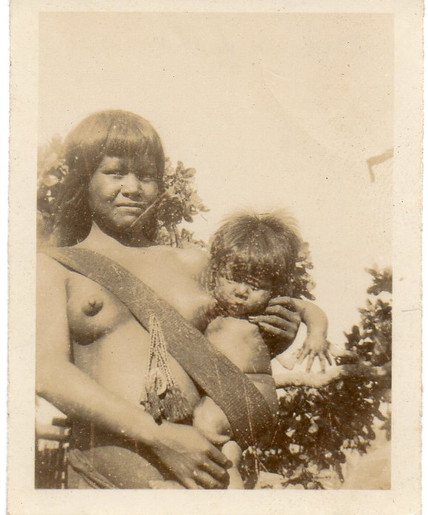

At the end of the afternoon, greeting the sunset, the girls leave the shed wearing red clothes, always serious and in posture, as a sign of respect. Dancing, they join the songs that announce their entrance. It is the beginning of another Moqueado festival, a centuries-old tradition celebrated annually among the Guajajara.

The Guajajara, the largest indigenous ethnic group in Maranhão, have a spiritual and physical relationship with nature. One of the most important moments for them is the transition from childhood to adulthood, celebrated at the Moqueado or Menina Moça festival. Its social and cultural field is established based on this relationship, in which all beings, living and non-living, share the same culture manifested in the sound of the maracás that carry the voices of the spirits, in the chants sung and in the dances present in the rituals.

The party lasts, on average, a cycle of one year, divided into phases that require time and organization for its preparation. The first is tocaia, the name given to the period when girls remain in isolation after menarche. At this stage, permission is sought from the owners of the land, through songs that announce the girls’ entry into the ritual process, which shows respect for the spirits and the abundance of the next stage: hunting. This is marked by the search for sufficient food – such as monkeys and poultry – for the celebration days, guaranteeing the last stage of the festival, characterized by the distribution of dumplings made from minced meat.

The days of the festival are marked by songs and dances that guarantee communication with the divine and produce meaning through physical and spiritual interaction with nature. The creation and transformation of the world are attributed to the supernatural, enchanted, or karuwaras. These may be the owners of the forest and the waters, the wandering spirits of people and animals that survive the death of the body and give meaning to rituals as a way of reaffirming life.

Animals are part of the Guajajara worldview. Many are a source of transformation for those who participate in the moqueado festival. An example of this is the monkey, an animal characteristic of the ritual that, when consumed, brings longevity to those who consume it. Another example is the tona, a bird whose meat is passed to the parts of the body where it sweats the most, to prevent girls from suffering from a bad smell during their lives. Even after the physical loss of the animal’s body, its spirit is still present, occupying the position of subject at the festivities, which is why care is so important during the hunting phase, in which the shared practices of traditional knowledge are carried out. Being silent, having attentive eyes and ears, protecting the body, not being afraid, taking shelter, walking and stopping are the procedures that determine the lives of hunters.

During the festival, the various forms of ornamentation reinforce the rapprochement between the Guajajara and the spirits. Body paints with jenipapa, feathers attached to the body, beaded jewelry, and other artifacts that refer to protection and rebirth are used. Girls’ hair bangs are also cut as a symbol of a new growth cycle. They are left behind, like something from childhood that dies, so that a new woman can emerge.

Women from the community play a prominent role in the celebration. They are responsible for the care during the tocaia period: during the party, when decorating the girls with headdresses filled mainly with macaw feathers and necklaces; and at the end of the ritual, when they prepare dumplings made from minced meat, a preparation technique that gives the party its name.

Moquear derives from the Tupi word, moka’em, which means ‘meat prepared on a grill’, and consists of a typically indigenous technique of smoking game meat as a form of preservation. Fire is understood as a purifying element that alters the condition of the animal’s flesh, since the spirit survives even after the death of the body. The complete elimination of blood by heat makes it impossible to express negative agency on those who consume it, especially when it comes to girls, who, because they are going through the preparation period, are more susceptible to the action of the karuwaras. During the preparation for the Moqueado Festival, the animals are hunted, treated and seasoned with salt, and only the viscera are removed, due to the time they are stored. On the day of the party, they are cooked, shredded and mixed with cassava, which produces dumplings made only with game meat. The way to handle the meat, the right temperature, the right time for boiling, cooking, separating and mixing with cassava constitute the knowledge that transforms moquear into a technique.

The transformative quality of the party takes place from the tocaia to the final moment of the celebration. It reaches its peak through the ornamentation of the initiates and the consumption of minced meat, which provide the incorporation of characteristics such as longevity, resistance, strengthening and protection, not only to girls, but to all those who experience the completion of this cycle. The social relations established during the ritual strengthen the cultural persistence of the Guajajara, the ancestry, and the continuity of the festival. They affirm the importance of the role of older women in the preservation and care of the feminine dimension of the community, expressing exchange, zeal, and affection within the ritual performed by and for women.

Thus, at sunrise, new women emerge. Dressed in white, symbolising the dawn that marks the end of one cycle for the beginning of another.

Lyssia Santos

São Luís, August 2023.

Sources:

SILVA, Elson Gomes from. The Tenetehara and their rituals: an ethnographic study in the Pindaré Indigenous Territory. São Luís, 2018

.

COELHO, Jose Rondinelle Lima. Tenetehara Tembé cosmology: (re) thinking narratives, rites, and alterity in the Upper Guamá River — PA

. 2014.

MORAIS, Letícia Leal Borges de. What the Tenetehara say: the gesture of the songs in Wyra’wha. Brasilia, 2018

.

PONTE, VanderLúcia da Silva. “Shaman woman”: cosmopolitics of the body at the Wira’uhaw Tenetehar-Tembé festival. 2022

.

FAUST, Carlos. People’s banquet: commensality and cannibalism

in the Amazon. 2002.

Akroa-Gamela

Diogo Guilherme Boyhe

National Library - Brazil

THE STRUGGLE OF THE AKROÁ-GAMELA PEOPLE OF MARANHÃO: CULTURAL RESCUE AND RECOVERY PROCESS

The Akroa-Gamela people, from Maranhão, are an indigenous group that has been inhabiting the Baixo Parnaíba region of Maranhão for centuries. The history of these people has been punctuated by struggles and challenges in relation to the recognition of their rights and the preservation of their cultural identity. The Gamela people currently live in six communities in the municipalities of Viana and Matinha, in Maranhão. Since the 18th century, the Gamela have suffered a process of great population loss and erasure.

Starting in the 19th century, with the expansion of the agricultural frontier and the arrival of non-indigenous people in the region, the Akroá people lost territories and had their alienation process intensified. The pressure on their traditional lands, combined with the absence of public policies aimed at the protection of indigenous peoples, created a scenario of conflict and marginalization. They were forced to face the invasion of their land, the degradation of the environment, and the destructuring of their communities.

At the beginning of the 21st century, with the enactment of the Federal Constitution of 1988, which recognized and guaranteed indigenous rights, the Akroa-Gamela people were faced with a new opportunity to fight for their territorial and cultural rights. The repossession of their traditional lands became a central agenda in the search for recognition and justice.

The recovery process was marked by great challenges and tensions, as it involved direct confrontation with squatters and landowners who had settled in indigenous areas irregularly. In addition to the context of territorial struggle, festivities play a central role in the culture of the Akroa-Gamela people. Celebrations are moments of artistic and cultural expression, in which ancient rituals, traditional dances, songs, and typical cuisine are preserved. The festivities are a moment of reaffirmation of Akroa-Gamela’s roots and resistance. The most important expression is the festival dedicated to the Afro-indigenous saint Bilibei.

Bilibei, Belibau or even Bilibreu, is a saint carved in wood and covered with pitch black dye. The enchanted person, worshiped in this ritual, is a mythical figure, primarily known as’ entrudo ‘, and is of central importance to the community. Bilibei is considered the guardian of health and fertility, fundamental aspects for the continuity and well-being of the people.

During the Bilibei ritual, the indigenous people travel through all the villages of the Taquaritiua territory in a race that lasts about 12 hours, known as the Bilibei Dog Race. On this journey, they paint their bodies and march in search of the “jewels”, vows to the promises made. Chickens, ducks and pigs are offered to the entity. In addition to the central activities of the ritual, other actions and discussions take place throughout the celebration days. The log race, the round of conversation with indigenous leaders, and the discussion about resistance to the installation of electric power lines in the territory are examples of how the Bilibei ritual is a political act.

The Bilibei ritual, which traditionally took place during Carnival, was transferred to the month of April as a way to remember the massacre that took place on April 30, 2017. In this tragic event, the Akroa-Gamela were attacked by a variety of actors, including politicians, members of the Protestant church, and farmers, resulting in a veritable massacre that left more than 20 wounded. Two indigenous people had their hands cut off. The transfer of the date to April became a symbol of the resistance of the people, in memory of these events.

References:

SANTOS, Sandra de Jesus dos. The Akroa-Gamela people and their struggle for territory in Maranhão. In: Geonorte Magazine, v. 5, n. 18, p. 1099-1110,

2013.

NUNES, Socorro Almeida. The Akroa-Gamela in Baixo Parnaíba Maranhão: ethnicity and territoriality. Doctoral Thesis. Federal University of Maranhão, 2011

.

OLIVEIRA, João Pacheco from. The indigenous presence in Maranhão: from invisibility to the claim of their territories. In: Anthropological Yearbook, v. 90, n. 2, p. 273-300, 1991.

ARAUJO, Laís Vitória. Struggle and resistance: the Akroa-Gamela and the retaking of their lands. In: Notebooks of Applied Social Sciences, v. 13, n. 25, p. 65-85

, 2015.

Krenyê

The Krenyê are part of the Timbira cultural complex, which is the name that designates a group of peoples that inhabit Maranhão, Tocantins and Pará: Canela Ramkokamekra, Canela Apanyekra, Apinayé, Parkateyê, Krahô, Krepum Kateyê, Krikatí, Pukobyê. Other Timbira groups no longer identify themselves as autonomous peoples, such as the Kukoikateyê, Kenkateyê, Krorekamekhra, Põrekamekra, Txokamekrá, Txokamekra, who gathered and culturally dissolved among some of the Timbira peoples mentioned above.

The name Krenyê means bird, parakeet, known to non-Indians as Jandaia. The German ethnologist Curt Nimuendajú (1946) considered the existence of two distinct peoples named Krenyê, which he differentiated into: Krenyê de Bacabal and Krenyê de Cajuapara. Based on the ethnohistorical map drawn up by Nimuendajú (1981), we can observe the presence of the Krenyê in the vicinity of the Mearim, Grajaú and Gurupi rivers, around the middle of the 19th century.

The departure of part of the current Krenyê from the region to which they refer to as Pedra do Salgado, near the city of Bacabal, was consolidated between the 50s and 60s of the 20th century, motivated by two factors, as demonstrated by stories and historiographic sources. First, the growing occupation by migrants in the Mearim River region, which had direct consequences on the remaining indigenous populations. The second factor was the measles outbreak to which they were affected, causing great mortality in these people. The survivors took refuge in areas where the Krepum Kateyê (TI Geralda) and Tenetehara (TI Pindaré) Indigenous Lands are currently located.

The advance of the expansion fronts combined with the outbreak of epidemics in this region of the Mearim River caused not only the departure of the Krenyê and their search for shelter in other Indigenous Lands, but also the social disaggregation of different Timbira peoples.

Over the past four decades, the political actions carried out by indigenous peoples in Brazil have made visible and concrete pressures to force the State to enforce territorial, ethnic and educational rights. A series of specific political mobilizations, the elaboration of representation mechanisms, the construction of alliances and the identification of elections constitute expressions of the struggles of indigenous peoples. The political battle of the Krenyê indigenous people began in 2004, based on their demands for land, framed in situations of conflict resulting from the coexistence on land of other indigenous peoples, and also from the interventions of bodies that become a protagonist of disputes and points of view. For more than a decade, the struggle of the Krenyê gave rise to many demands, either through actions, in the legal field, or through direct confrontation for ethnic recognition and territorial rights.

Finally, in 2019, they had their land demarcated, after a long mobilization process, which has guaranteed the continuity and the resumption of their cultural patterns through songs, dances, rituals, agricultural activities and the production of handicrafts.

João Damasceno Gonçalves

São Luís, August 2023.

Krepyn Kateyê

KREEPYN KATEJE (Krepumkateyê)

Kreepym-Katejê or Krepumkateyê (Krepum), the monkey people — currently also known as the Timbira people — belong to the Jê linguistic family, the Macro-Jê trunk. Timbira is the name that designates a group of peoples: Apinayé, Canela Apanyekra, Canela Ramkokamekra, Gaviao Parkatejê, Gaviao Pykopjê, Krahô and Krinkatí. Other Timbira ethnic groups no longer present themselves as autonomous groups: the Krenyê and Kukoikateyê live between the Tembé and Guajajara, who speak a Tupi-Guarani language (Tenetehara); the Kenkateyê, Krepumkateyê, Krorekamekhra, Põrekamekrá, Txokamekra gathered and dissolved among some of the seven Timbira peoples initially listed.

Like the Krenyê, the Krepumkateyê were also known as Timbira for a long time, becoming self-denominated Krepumkateyê only in the mid-1990s, when they already had their land demarcated. The Krepumkateyê did not lose their territory and were able to demarcate their land, the Geralda Toco Preto Indigenous Territory, in 1994. Since 2017 — in Itaipava do Grajaú.

The Krepumkateyê (Krepym = proper name of a lake; it would refer to a place where the emus lay (fart) eggs (kre)) lived near the place formerly occupied by the Caracategé, on the Grajaú River, and were probably descendants of them.

References

FIGUEIREDO, João Damasceno Goncalves. We want to tell the whole of Brazil that we are alive and exist: the process of ethnic affirmation and the struggle for territory of the Krenyê in Maranhão. (Master’s thesis) Master’s degree in Social Sciences, State University of Maranhão. Available at: < https://repositorio.uema.br/bitstream/123456789/736/3/JOÃO%20DAMASCENO%20GONÇALVES%20FIGUEIREDO%20JÚNIOR_1%20-%20PDF-A.pdf >. Accessed on: August 07, 2023.

NASCIMENTO, Luiz Augusto Sousa from. Dispersion, coalescence, and ethnicity of a Timbira group: the Krenyê weaving paths to ethnic and territorial (re) knowledge. In: Brazilian IFP Scholarship Meeting – São Paulo, Carlos Chagas Foundation,

2010.

Hawk

THE PYHCOP CATIJI HAWKS

Hawkeye call themselves Pyhcop catiji (spelling used by indigenous teachers), which means’ people ‘or ‘staff of the hawk’. Currently, they live in the Amazon of Maranhão, are part of the Jê Timbira linguistic-cultural complex and are located in the Governador Indigenous Territory, covering 41,642 ha, in the municipality of Amarante do Maranhão, between the Krikati and Arariboia Indigenous Lands.

The Governador Indigenous Territory had its area demarcated in 1977 and approved in 1982. It currently consists of 10 villages: Aldeia Governador, Aldeia Rubiácea, Aldeia Riachinho, Aldeia Nova, Aldeia Monte Alegre, Aldeia Água Viva, Aldeia Canto Bom, Aldeia Novo Marajá, Aldeia Dois Irmanos and Aldeia Bom Jesus.

In recent years, the relationship between the Gavians and the population of Amarante, the nearest city, has become increasingly tense, due to the process of reviewing and expanding the boundaries of the Indigenous Land, combined with the constant conflicts with loggers who use an access route through the villages surrounding the reserve, to practice the illegal removal of wood within the area.

The increase in the population of Hawks, the increasing pressure of predatory activities surrounding the Indigenous Territory and the reduction of hunting, fishing and gathering areas hinder the reproduction of ways of doing and living, which impelled the Pyhcop Catiji to request, since 2003, the revision and expansion of territorial limits.

The Gavião villages have a circularity peculiar to the Timbira people, with a central circle, which is the courtyard, where rituals, ceremonies and meetings take place. This courtyard is connected by radial paths to a larger circle in which the houses are arranged.

One of their main rituals is that of the Wyty masks, which are developed from halves and ceremonial groups. During the ritual, participants are divided into ceremonial groups that relate through collective actions. In this rite, in addition to the associated girl, two young people are chosen as “Hawkeye”, they are the Hýcre, and a boy is chosen as a “baby chick”, the Intoo. Both remain in seclusion throughout the ritual, separated from their families and only work when the women of the village request it. At the end of each day, they go around the houses of the village to receive the food offered to them, a routine that extends over the months of seclusion in the ceremonial house.

Another rite of passage is the Pyr pex or Festa da Barriguda, as the tree from which the log is removed for the race is known. The ritual consists of closing to protect the mourning of the family and of the entire village to which the person who died belonged. During the mourning period, there are a series of precepts that must be complied with, such as the use of body paint, the haircut, and other restrictions and determinations.

The Pyr pex symbolizes the continuity of the cycle of life and of the political and ceremonial daily life, with the end of the protection of mourning and the reintegration of the widow, the relatives of the deceased and the entire community into everyday social life, which begins with the preparation of the “soul of the dead” to reach the village of the dead and ends with the belly log race.

João Damasceno Gonçalves

São Luís, August 2023.

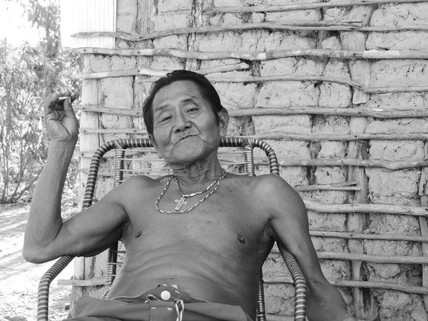

IRENE GAVIÃO

I am Irene Gavião and I was born in the old location of the village of Riachinho on April 28, 1965. My name, in the indigenous language, is Mypaw (read ‘mampau’). Having this name means that I am part of a specific group that receives the ritual of initiation to adulthood, unlike other groups of names, within the Gavião people of Maranhão. This ritual, called Wy’ty, is one of the largest and rarest, and only a few names receive this honor. My Wy’ty ritual began when I was a very young child, still not understanding it properly, and was completed at the end of my adolescence. I married when I was 17 and soon had my first child. Today, I have eight children, many grandchildren, and a few great-grandchildren. After all the births, I always kept my guard safe, as this is a very sensitive period for the body and for the baby. Keeping safe also helped me to be a good runner with Tora (Pyr Pex), and I was a great runner! When other ethnic groups came to compete in Tora races in our territory, I was always ahead. The North American missionaries arrived in the Governador village and later in the village of Riachinho, shortly after the time when we were suffering from measles, yellow fever, and cancer. Many of our people died. In my family, there were only two women left: my mother Germana and my aunt Maria Amélia. We were part of a Timbira group called Rõocu Cati Ji, but we were few in number and were assimilated to the Pyhcop Cati Ji. Today I’m going to be a singer for four years. I decided to learn because I realized that I should represent my village and the Gavião people of Maranhão, since our elderly singers were dying one by one. Since I didn’t bother to learn when I was young, I learned to sing by listening to my relatives. Today, I am the chief of the Monte Alegre village with great pride.

Irene Gavião

Aldeia Monte Alegre, August 2023

WYTY: The Songs of Resistência Gavião Pykopjê

Warao

WARAO

The Warao, whose meaning refers to ‘people of the water’, originate from Venezuela and are considered the second largest indigenous people in the country, with approximately 48,000 people.

The mother tongue is also called Warao. Like the ethnic group itself, it is in a vulnerable situation. Cultural erasure movements have been effective, especially among young people, who have started to communicate only in Spanish, the official language of Venezuela.

The Warao people are traditionally inhabitants of the Orinoco River Delta (Venezuela). Recently, the Warao Population Flow Monitoring Report (IOM, 2020), carried out in partnership between the Government of Maranhão and the United Nations Migration Agency (IOM), traced the mobility of these indigenous people from migratory routes departing from Venezuela. The survey reached three cities in which the Warao established housing: São Luís, Imperatriz and São José de Ribamar, referring to March 1 and 9, 2020 (IOM, 2020, p.1).

According to the local government, the Warao are also in eight other municipalities in the state: Santa Inês, Paço do Lumiar, Pinheiro, Barreirinhas, São Mateus, Bom Jardim, Estreito and Açailandia. It should be noted that the Warao indigenous migration in Brazil has been characterized precisely by complex flows through various states and municipalities.

Most families are made up of the reference person, partner, and children. On average, each family has four members. We also observed that 31% of families are single parents. The composition of the Warao families that are in Brazil, in the state of Maranhão, is different from the family composition of those who lived in Venezuela, indicating that only part of the members of the original family migrated to Brazil. The average number of members of the family nucleus in Venezuela, reported by the interviewees, was 10 members; in Brazil, these family groups have, on average, four members.

According to data compiled by the R4V Platform, more than 5,000 indigenous Venezuelans have arrived in the country since 2016 through the northern border, and approximately 65% of them are from the Warao ethnic group. In Venezuela, it is estimated that there are more than 50,000 indigenous people from this ethnic group. The Warao population is present in the five regions of the country, but until today few initiatives have sought to better understand the profile of these indigenous people on the move and none had focused on their arrival in Maranhão.

References

BRITO, Jaciara Neves; BARROS, Valdira. Public policies for the reception of Venezuelan Indigenous Warao refugees by the state of Maranhão. Available at: < http://www.joinpp.ufma.br/jornadas/joinpp2021/images/trabalhos/trabalho_submissaoId_1365_1365612edff3b7b81.pdf >. Accessed on: August 07, 2023.

CARVALHO, Vivian. The Warao language in the state of Pará. In. NEVES, Ivania. Portraits of the contemporary: indigenous languages in the Amazônia Paraense. Final Report, FIDESA/SECULT/LEI ALDIR

BLANC, Belém, 2021.

DURAZZO, Leandro Marques. The Warao: from the Orinoco Delta to Rio Grande do Norte. Indigenous Peoples of Rio Grande do Norte. 2020. Available at: < http://www.cchla.ufrn.br/povosindigenasdorn >. Accessed on: August 8, 2023.

Warao Population Flow Monitoring. International Organization for Migration (IOM), 2020. Available at:. < https://www.globaldtm.info/ > Accessed on: August 07, 2023.

ROMERO-FIGUEROA, Andrew (2020). The Warao-Spanish contact. Considerations on the process of lexical acculturation of the native language of the Orinoco Delta. Spanish Academic Publishing. Pp. 65. < https://periodicos.sbu.unicamp.br/ojs/index.php/liames/article/view/8661196/23039 >ISBN 978-620-0-38531-4. Available in:. Accessed on: August 07, 2023.

The Warao of Upaon-açu

Canela Rankokamekra and Apanyekra

CANELA RANKOKAMEKRÁ and APANYEKRÁ

The term Canela is used by the white man for three East Timbira peoples: Rancocamekras, Apanyekras, and Kenkateyés. Originally, the term Canela was associated with Capiecrans, also called Ramkokamekras. Currently, the self-designation that unifies the three peoples is Memortum’re.

The Canela speak a language of the Jê family, the Macro-Jê trunk, with minor variations. They can easily understand Krikati/Pukobyé and Gavião, from Tocantins, the main surviving East Timbira languages. However, Apinayé (Western Timbira) is very different from Canela, similar to Spanish in relation to Portuguese.

The Ramkokamekras live in the village of Escalvado, known as Aldeia do Ponto, about 70 km south-southeast of Barra do Corda, Maranhão. The Canela Indigenous Territory was approved and registered and is located in Fernando Falcão, a new municipality. It is bounded by the Serra das Alpercatas and the Corda River.

The Apanyekras inhabit the Porquinhos Indigenous Territory, regulated in the 1980s, which is located about 80 km southwest of Barra do Corda, Maranhão. These people have a diversified ecology, with forests and scrublands, in addition to the Corda River, for agriculture, fishing and hunting.

Before contact with whites, Timbiran nations were estimated to have lived in groups of 1,000 to 1,500 people, but were divided due to conflict. In 1817, the Kapiekran (ancestors of the Ramkokamekras) declined due to wars and smallpox. In 1936, there were about 300 Ramkokamekras, increasing to 1,387 in 2000. The Apanyekras, on the other hand, were estimated at 130 individuals in 1929, and they registered 458 in 2000.

Source:

ADAMS, Kathlen; PRICE JUNIOR, David (Eds.). The demography of small-scale societies: case studies from lowland South America. Bennington: Bennington College, 1994. 86 p. (South American Indian

Studies, 4)

CROCKER, William H. Canela (Central Brazil). In: WILBERT, Johannes (Org.). Encyclopedia of World Cultures. v.7. New York: G. K. Hall & Co., 1994, p.94-8

.

——–. Stories from the pre- and post-pacification periods of the Rankokanmekra and Apaniekra-Canela. MPEG Bulletin: Anthropology Series, Belém: MPEG, n.68,

1978. 30 p.

——–. The Messianic Canelas movement: an introduction. In: SCHADEN, Egon (Org.). Brazilian ethnology readings. São Paulo: Cia. Editora Nacional, 1974. p.515-28. [Translation of the original in English published in the Proceedings of the Symposium on Amazonian Biota, v.2 (Anthropology),

pp. 69-83, 1967].

——–. The non-adaptation of a savanna Indian tribe (Canela, Brazil) to forced forest relocation: an analysis of ecological factors. In: BRAZILIAN STUDIES SEMINAR (1st.: 1971). Annals. v.1. São Paulo: Institute for Brazilian Studies, 1972. p. 213-81

.

NOT YUNDAJU, Curt. The Eastern Timbira. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1946. 357 p.

OLIVEIRA, Adalberto Luiz Rizzo from. Ramkokamekra-Canela: domination and resistance of a Timbira people in the Midwest of Maranhão. Campinas: Unicamp, 2002. (Master’s Dissertation

)

QUEIROZ, Maria Isaura Pereira de. Social organization and mythology among the Timbira of the East. Rev. of the Institute for Brazilian Studies, São Paulo: USP, n.9, p. 101-2, 1970.

Kokrit

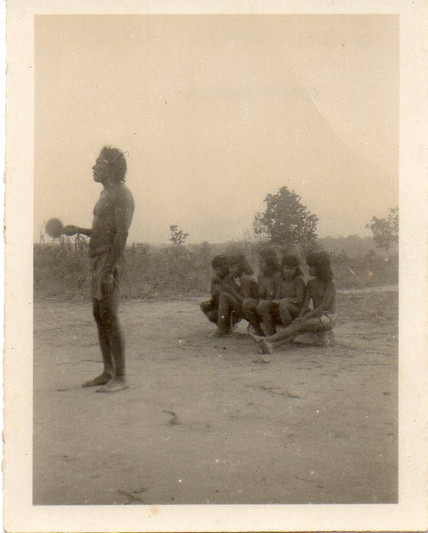

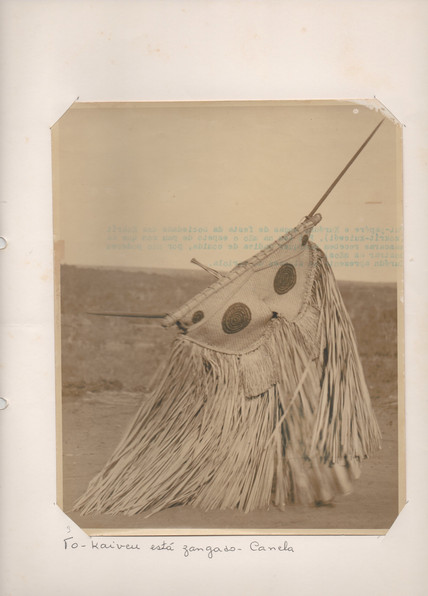

THE KOKRIT MASK RITUAL

The Ramkokamekra Mask Festival, known as Kokrit or Kokrit-ho, is a ceremonial celebration that takes place during the summer period in the dry season. The Ramkokamekra, the indigenous people of Brazil, celebrate this festival, which consists of five major amji kĩn (festivities), one of which is dedicated to the Kokrit.

The Kokrit ceremonial society is composed of about thirty members and their participation is transferred matrilineally, together with their personal name. This society is responsible for creating and using mask-garments, which are the personification of enchanted rivers, part of its cosmology. The festival of masks is a way of honoring them and getting in touch with the spiritual world. During the party, the masked men play the enchanted people of the river, behaving in a peculiar and enigmatic way.

Before the festival, members of the Kokrit society meet at a ranch far from the village to make masks using buriti straw. This process takes about two months, during which they do not cut their hair or dye themselves. The masks are custom-made, according to the owner’s height, covering him completely, including his feet. Curt Nimuendajú (1946) and Reis and Lima (2003) described 12 types of masks, based on the lines of the eyes, which are made with charcoal, jenipapa and annatto tinctures. The drawings correspond to the ontological qualities of the being that the mask embodies. Each model has a specific function, such as Ihô-kênre (master of ceremonies), Tocaiweure (runner) and Kempej (group leader).

After making the masks and painting their eyes, the masked men line up to the village, where they are greeted by women, who act as ‘mothers of the mask’. Each masked man chooses his mother, who will feed him throughout the party, providing meat and other food whenever he wants.

Two young women are chosen as ‘queens of the party’ and also participate in the celebrations, dancing with their own masks called Mekratamtúa. The festival lasts several weeks or a month, always taking place during the summer, when the rain has stopped.

With the end of the period of games and dances, the party ends with a big celebration in which the masked men place their capes next to the muquia (big berubu), where everyone eats, sings and dances during the night. Finally, the cloaks are removed and each owner can reuse the straw or dispose of it.

The Kokrit have a peculiar behavior during the party, being generally silent or emitting a soft trill. They communicate with each other and with others through movements with the edges of the mask. They express contentment by dancing and waving their bangs, and when embarrassed or irritated, they may lower their heads or threaten with their horns.

The Kokrit festival is a rich and significant tradition for the Ramkokamekra people, allowing them to connect with their beliefs, customs, and ancient way of life. The celebration also plays an important role in preserving the memory and identity of the Canela people.

RESUMES ARE CHALLENGES

The revivals challenge a story that the heirs of colonization dedicated themselves for centuries to making the only one acceptable. To justify their heritage, they must avoid any doubt that the conquest has ended and was successful. To guarantee their heritage, they need the true lords and owners of the land to be gone forever. They also need that, if there are any survivors, they have accepted complete surrender. They need, however, that this not be called surrender. This can remind you that there was a war and that, after all, your inheritance is booty, or even remember that the war is not over.

The revivals also challenge what is the main legacy of colonization, which is a very small capacity to imagine how to be in the world and to see who lives in it. The heirs of colonization received an immense collection of institutions and technologies so as not to see what is beyond the mirror, and not to hear what is around.

The reshows defy silence. Even with so many tongues cut out, interdicted, the voices of those who fell down echo and claim what was stolen from them.

The retakes challenge us to recognize the absurdity and violence of the extinction of peoples. Every people invents and reinvents themselves. There are people who make the history of their inventions their authenticity, celebrating their rebirths and proclamations. Then they accuse others of being invented and demand that they prove their past and present existence. At the same time, they invest all their strength, often brute force, to prevent others from existing. They steal land, prohibit languages, condemn religions, subject them to misery and slavery, and then charge them for not having been immune to history and bearing their marks on their faces. They force them to be silent, to flee, to hide, and then they charge them for having been slow to show up.

The retakes are a challenge to attempts to throw those who have always been here into oblivion. Since at least the 18th century, we have known that the Akroá Gamella live in the north and east of Maranhão, in addition to Piauí. Since at least the 17th century, we have known that the Tremembé live on the coast of Maranhão, Piauí and Ceará. Since at least the 17th century, we have known that the Tupinambá live almost all along the Brazilian coast. In Maranhão, they were the first to find the colonizers, who tried to eliminate and arrest them in the past, but they are still on the island of São Luís and the Baixada. Since at least the 17th century, we have known that the Anapuru Muypurá live in Baixo Parnaíba. Since at least the 17th century, we know that the Kariri have been in almost the entire Northeast of Brazil and that, since the 60s of the last century, the Kariú Kariri have been in the south of Maranhão and in Tocantins.

In those centuries, they have faced attacks on their bodies and their land. They were targets of greed for their work, their territory, and often punished for their resistance. The State has already made them enemies of war, it has tried to “pacify” them, it has already recognized and denied them the right to land and, to try to put an end to history, they have even declared their extinction. Despite this, they are still alive, growing, with their feet firmly on the ground.

The retakes challenge us to break with everything that supports the legacies of colonization, to open eyes and to remember that Brazil and Maranhão are Indigenous Lands. The floor we walk on, the one below and on top of it, has many owners. Retreats challenge us to recognize which are the true ones.

Guilherme Cardoso

São Luís, July 2023.

Anapuru Muypurá

HISTORY OF THE ANAPURU MUYPURÁ DO MARANHÃO PEOPLE

In 1684, the Anapuru people were already living on the land of the current city of Brejo – MA and fought against the Portuguese colonizers who wanted to invade their territory.

At the time, the provincial government issued several official orders to wage war against the indigenous people, considered “Tapuia barbarians”. Many conflicts and wars were faced against the colonizers.

From the beginning of colonization, the Anapuru people resisted as much as they could the attempts of the colonizers to “reduce it and finally pacify it”. The resistance of the indigenous people was, without a doubt, the greatest obstacle. The frequent attacks against whites were their defense response to what they considered, and still consider today, the invasion of their land and violence against the people.

Persecutions, massacres, enslavements, and institutionalized ethnocide helped the Anapuru Muypurá to be considered “extinct” since the 19th century, leading to the erasure and silencing imposed on the history and presence of the Anapuru Muypurá people.

Currently, the Anapuru Muypurá are dispersed in various rural and urban areas of the state of Maranhão. However, the population has a greater concentration of families in Brejo, Chapadinha and other municipalities in the Baixo Parnaíba region. There are also families in the states that border with Maranhão: Pará, Piauí, and Tocantins.

The context of social invisibility of the Anapuru Muypurá people began to change in 2019, when they began to reorganize themselves politically and establish constant relations with the Indigenous Missionary Council (CIMI) and with the other indigenous peoples in the process of retaking in Maranhão (Akroá Gamella, Tremembé do Engenho e da Raposa, Kariú Kariri and Tupinambá).

The Anapuru Muypurá began to investigate their own history, “digging up memories” and publishing them on social networks and resumed the fight for their original rights, the first of which was to the land.

One of the central aspects of the Anapuru Muypurá identity is the memory of a common origin that connects them to the time of the old Brejo dos Anapurus village.

Each family keeps the history of the people alive, through the genealogy of their indigenous ancestors persecuted and kidnapped during the colonial wars against the Anapuru. The elders are the main guardians of these memories, they who transmit them to their descendants, from generation to generation.

The Anapuru Muypurá indigenous people were excellent potters and connoisseurs of the art of ceramics. They produced pots, bowls, quarries and clay pots. The “Olaria Velha” of the Brejo dos Anapurus village was where the Olaria community is today, in Brejo – MA. At that time, men worked in the manufacture of bricks, adobes and tiles, and women with the production of pots and other crafts made of clay.

Today, it is still possible to find healers/shamans/healers who make blessings, bottles, baths and medicines “from the forest”, and those who worship the enchanted, such as Mães d’Aguas, Curupira, Caipora, Caboclos Índios, Enchanted Snakes and Cabça de Cuia. In addition to the Anapuru Muypurá indigenous people who produce straw and clay handicrafts.

The “being Anapuru Muypurá” has been reconstructed throughout this process of recovery and is influenced both by the past – the memory of the elders and the knowledge transmitted by them – and by the present – the struggles and demands for original rights.

Lucca Anapuru Muypurá

Chapadinha, August 2023.

“Muypurá means ‘fruit of the river’. We are fruits that sprout in freshwater currents, which at the same time as they feed, reforest the Earth with our stubborn seeds. Our elders are engineers of the ciliary forests. Its roots feed on the river’s waters, while at the same time they are also a strength for the same river to remain abundant. The Anapuru Muypurá people are ‘igá’ (ingá), the fruit of the Ingazeiro Velho who was born on the banks of the river. A single ingá can carry dozens of seeds in the pod. Seeds that insist on resisting/existing.

” – Lucca Anapuru Muypurá

Tremembé

THE HISTORY OF STRUGGLE AND RESISTANCE OF THE TREMEMBÉ PEOPLE OF ALDEIA ENGENHO

Attacks on indigenous peoples are known worldwide for the history of violations and violence that began with the arrival of the colonizers. With the Tremembé people it was never different and, due to various unfavorable political and institutional contexts in Brazil, they survive fighting daily against any form of erasure.

The Tremembé are extremely warlike and resistant to terrible massacres. It is important to highlight the great genocide suffered by this people and their sacred soil, even suffering from the process of renaming their territory, formerly called São José dos Índios – mainly because of its occupation by the Tremembé and Tupinambá peoples – today, the city of São José de Ribamar. As if so much violence were not enough, the Tremembé were violently massacred and were even placed in rows in front of the cannon to die.

The Tremembé do Engenho Traditional Territory is fighting an arduous struggle for its rights in order to continue living its history full of ancestry, culture, ways of life, religiosity and enchantment. Fighting against various forms of usurpation of their rights, such as land grabbing, real estate speculation, various invasions, pollution of the Ubatuba River, environmental devastation, among others.

Located in the metropolitan region of Upaon-Açú Island (São Luís), in the city of São José de Ribamar (MA), they have an area of 74,000 hectares, where 47 families live who grow their food for their survival and also supply two major fairs in the region. They also promote the manufacture of handicrafts, political and cultural activities designed and carried out by the people themselves, as a way of strengthening their original and ancestral traits.

Currently, the Tremembé Territory is being studied, precisely at the stage of drafting the report for approval by FUNAI (National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples), an achievement devised by many hands, supporters together with the people, and of its political organization, which is consolidated through the Tremembé Leadership Council.

And it is in this perspective and acting in unity that we propagate and strengthen the struggle of indigenous peoples and echo our voices, always fighting for the rights, respect and dignity of all peoples.

Raquel Tremembé

São Luís, August 2023.

Tupinambá

TUPINAMBÁ ON THE COAST OF MARANHÃO

Much is said about a gigantic indigenous nation that was exterminated in Maranhão. Would it really be possible to exterminate a nation?

In Cururupu, a city whose name originates from Tupi, the story of Cabelo de Velha is told.

The Tupinambá leader who fought for his territory, gave his life for his people and died fighting. It’s our oldest ancestor.

We are located on the islands, towns and villages in the bowels of Cururupu and Guimarães, in the Baixada Maranhão region. We do not live on lands demarcated as indigenous and are outside the stereotype placed on “indigenous peoples”, because we were not included in any political right as such. The ancestral recovery of the Tupinambás in Maranhão is true, because we have by right, at any time, the power to rise up.

Forced silencing and erasing causes us to keep away what is inside us. This nation, so sung in the Maranhão tunes, was the first to have its blood shed, which is under its feet. People forget that stubborn seeds sprout even in concrete. So are we, we continue to sprout like our ancestors, and to fight, now with other weapons.

To take back is a legitimate right for a people that have been massacred. Tupinambá is called upon to get up and only through us is this possible, because we are the continuation. Courage is an inheritance, and our story does not begin today. It comes from our great-grandparents and great-great-grandparents who left us wisdom such as straw, medicinal herbs, artisanal fishing and the self-cultivation of our own food. The struggle also lies in resisting the attacks of those who can’t stand our existence and uprising, and on the State itself, which continues to silence those from their lands.

Amanda Tupinambá

São Luís, August 2023.

Museum of the Person

Indigenous Lives in Maranhão

The Museum of the Person is a virtual and collaborative museum of life stories. Since its founding in 1991, it has been a space dedicated to transforming the stories of each and every person into a world heritage. The Museum systematized its practices to transform them into a Social Technology of Memory, in order to guarantee the right of every group to record, preserve and disseminate their memories as part of the historical narratives of society.

The actions that gave rise to the Maranhão Indigenous Lives project were developed by the Museu da Pessoa in partnership with the Vale Cultural Institute. Its implementation is in line with Vale’s Social Ambição Commitments to support indigenous communities in the elaboration and execution of their plans in search of the rights provided for in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and initiatives to preserve and value culture are part of this commitment.

The project involved the involvement of local traditional leaders and indigenous organizations that work with the villages of Terra Indígena (TI) Pindaré, TI Alto Turiaçu and TI Caru. The participating peoples were Guajajara, in the municipality of Bom Jardim; Ka’apor, in the municipality of Zé Doca; and Awa-Guajá, in the municipality of Alto Alegre, all in Maranhão.

The objectives were to carry out mobilization and training actions; to record and disseminate the life stories of the elderly by young people. With this, it aimed to contribute to the appreciation of the memories of people whose knowledge and activities constitute the culture of these peoples and to strengthen the link between generations as a way of contributing to their causes.

In all, 41 young people were trained and 70 life story interviews were conducted, in addition to circles of stories recorded with the communities of the three peoples. The participants were trained using the Social Technology of Memory developed by the Museum of the Person and audiovisual techniques.

The experience of these young people resulted in the conception and organization of documentaries, where excerpts from the interviews selected by them during the training process describe the individual and collective trajectories experienced in this territory.

Based on the development of the autonomy and leadership of the groups, the participants engaged with the Guardians of Memory movement with the objective of continuing and expanding the memory actions built throughout the project.

Through local musealization – Forest of Stories, where for each person interviewed, a tree was planted and a plaque was installed with reference to their life history, this movement also promoted the socialization of stories, connecting their memories to issues of socio-environmental preservation.

We invite you to watch these stories produced by young indigenous people who find in the ancestry of their peoples the strengthening of their identity.

Museum of the Person

Indigenous Lives Maranhão - Awa-Guajá people documentary

Indigenous Lives Maranhão - Ka'apor people documentary

Indigenous Lives Maranhão - Guajajara People Documentary TI Pindaré

Indigenous Lives Maranhão - Documentary by Povo Guajajara TI Carú

Objects that produce bodies and people