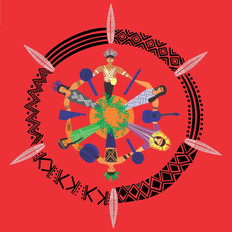

Indígenas.br - Indigenous Music Festival 2022 - 26/08

The unprecedented gathering of elders, elders, and spiritual leaders from different ethnicities marks the third day of the festival.

15:00 — Vocal Polyphonies Workshop with Cafurnas Fulni-ô (PE)

17:00 - House of Memory

Meeting with spiritual leaders, elders and elders from different peoples:

Atiã Pankararu (PE)

Owner of traditional knowledge, singer, and invaluable leadership of the Pankararu people; Fernando is responsible for Terreiro do Poente, whose function is to practice and host traditional rituals of the secrets of the Pankararu people and indigenous manifestations of the tradition of Cansanção, in the Umbu Race, the main rites and festivities of its people.

He

is also an art educator at the Pankararu Indigenous School, where he teaches children and adolescents about culture, such as handicrafts, contributing to the strengthening and maintenance of the community. Atiã was in the United Kingdom and Switzerland for cultural exchanges as a representative of the indigenous peoples of Brazil.

Thulni Fowá (Fulni-o-PE)

Karangre Xikrin (PA)

‘Mei’ is a word that designates a set of values essential to the Xikrin, the people who live at TI Xikrin do Cateté, in the south of Pará. People with traditionally strong social organization, with different roles between men and women, specific roles for each age group, and strategic qualities for their leaders, the Xikrin have always shown great concern with the beauty and correctness of what surrounds them.

D. Floriza and Roseli (Guarani Kaiowá/MS)

Floriza de Souza was born in 1960 in Cuchui Yvygua on the banks of the Yguarusu River, now owned by the Kaiowá Mission. His father Isaque de Souza was a Kaiowa and his mother was Monika Duarte, Guarani. With the arrival of the non-indigenous people and the expulsion from their lands, her Patron grandmother from Piraju and her grandfather Alexandre do Paraná went to the Dourados Indigenous Reserve. Floriza learned the Guarani prayers from her grandmother Petrona and from her paternal grandfather, Zacarias de Souza Brites, the Kaiowá prayers. Floriza studied at the reserve school and married Jorge da Silva at the age of 14, with whom she had 6 sons and 1 daughter. Until 2000, Floriza prayed at her father’s prayer house. In 2002, after the death of her father, she built her first prayer house with her husband, renovated in 2010, which lasted until 2016. Today, Floriza is a reference in the social and ritual life of the Jaguapiru village. She sings, dances and prays with her family members and likes to talk about her culture. Indigenous and non-indigenous people seek it to bless themselves and hear their prayers. Floriza also calls herself a “teacher” in her community because she brings together her grandchildren and other children to teach them about traditional Kaiowá culture, especially about the importance of the earth, of the newborn’s placenta buried in the ground, and about medicinal plants.

Floriza de Souza was born in 1960 in Cuchui Yvygua on the banks of the Yguarusu River, now owned by the Kaiowá Mission. His father Isaque de Souza was a Kaiowa and his mother was Monika Duarte, Guarani. With the arrival of the non-indigenous people and the expulsion from their lands, her Patron grandmother from Piraju and her grandfather Alexandre do Paraná went to the Dourados Indigenous Reserve. Floriza learned the Guarani prayers from her grandmother Petrona and from her paternal grandfather, Zacarias de Souza Brites, the Kaiowá prayers. Floriza studied at the reserve school and married Jorge da Silva at the age of 14, with whom she had 6 sons and 1 daughter. Until 2000, Floriza prayed at her father’s prayer house. In 2002, after the death of her father, she built her first prayer house with her husband, renovated in 2010, which lasted until 2016. Today, Floriza is a reference in the social and ritual life of the Jaguapiru village. She sings, dances and prays with her family members and likes to talk about her culture. Indigenous and non-indigenous people seek it to bless themselves and hear their prayers. Floriza also calls herself a “teacher” in her community because she brings together her grandchildren and other children to teach them about traditional Kaiowá culture, especially about the importance of the earth, of the newborn’s placenta buried in the ground, and about medicinal plants.

Roseli Concianza Jorge is the spiritual leader of the Kaiowá people, the great-granddaughter of Pa’i Chiquito, founder of the Panambizinho community in Mato Grosso do Sul. Roseli is currently the person most engaged in promoting ritual chants in the Panambizinho Indigenous Territory. She is one of the main connoisseurs of ñevanga, a therapeutic ritual based entirely on words. “This ritual was much more valuable, and now few trust it”, complains our interlocutor, explaining that doctors, nurses, and health workers have pushed traditional therapies into limbo. Roseli and her husband are known for their engagement in the fields of social and ritual life. Even though she is prevented from leading the long Corn Festival prayer because she is a woman, she is a prayer scholar and is preparing to direct it.

Roseli Concianza Jorge is the spiritual leader of the Kaiowá people, the great-granddaughter of Pa’i Chiquito, founder of the Panambizinho community in Mato Grosso do Sul. Roseli is currently the person most engaged in promoting ritual chants in the Panambizinho Indigenous Territory. She is one of the main connoisseurs of ñevanga, a therapeutic ritual based entirely on words. “This ritual was much more valuable, and now few trust it”, complains our interlocutor, explaining that doctors, nurses, and health workers have pushed traditional therapies into limbo. Roseli and her husband are known for their engagement in the fields of social and ritual life. Even though she is prevented from leading the long Corn Festival prayer because she is a woman, she is a prayer scholar and is preparing to direct it.

Dirce Jorge (Kaingang)

Dirce Jorge is Kaingang, Pajé (Kuiã) and manager and curator of the Worikg Museum of the Vanuíre Indigenous Land. The Worikg Museum is an initiative of three indigenous women from the same family from Kaingang, whose purpose of life is to fight for the indigenous cause and promote their Kaingang culture. The Workg Museum was born for this purpose. The collection belonged to Jandira Umbelino, whose indigenous name was Nhã Nhaty, matriarch of the family who died four years ago. There, in addition to the objects from the collection, there is what is not touched, but only felt. It is located in the Vanuíre Indigenous Territory, in the municipality of Arco-Íris, west of the state of São Paulo.

Dirce heard from her mother throughout her childhood that she couldn’t sing. Jandira Umbelino, from whom she inherited the Pajelança, was afraid that the whites would hear her daughters and sons sing in the indigenous language and kill them, as they did decades ago with so many other Kaingang. In Dirce’s case, the warnings sounded like punishment. She insisted on listening to the melodies in her mother’s voice and, after promising not to sing in public, added her voice to the lyrics in the original language.

“My mother was a book for me,” says Dirce, the only brother who followed her mother’s legacy, even though she was unable to learn the entire language. “While she lived, I stayed by her side learning everything she knew, from singing to cooking. We are already born Kujan (female version of Pajé), we are chosen. We were born with strength and no one is safe, so as a child I already knew that I wanted to do everything my mother did and more”.

Jandira spent decades hiding her culture out of fear of non-indigenous people. She wrapped her handicrafts, garments, necklaces, and headdresses in various cloths and stored them. In 2016, Dirce says, her mother became enchanted, leaving the world of the living. She has since taken over the management.

Mediation: Idjahure Kadiwel